[Part 1] Amplifying generalist research via forecasting – models of impact and challenges

This post covers our models of impact and challenges with our exploration in amplifying generalist research using forecasting. It is accompanied by a second post with a high-level description of those models, and more detailed description of experiment set-up and results.

Many of the world’s most pressing problems require intellectual progress to solve \[1\]. Finding ways to increase the rate of intellectual progress might be a highly promising way of solving those problems.

One component of this is generalist research: the ability to judge and synthesise claims across many different fields without detailed specialist knowledge of those fields, in order to for example prioritise potential new cause areas or allocate grant funding. For example, this skill is expected by organisations at the EA Leaders Forum to be one of the highest demanded skills for their organisations over the coming 5 years (2018 survey, 2019 survey).

In light of this, we recently tested a method of increasing the scale and quality of generalist research, applied to researching the industrial revolution \[2\], using Foretold.io (an online prediction platform).

In particular, we found that, when faced with claims like:

“Pre-Industrial Britain had a legal climate more favorable to industrialization than continental Europe”

And

“Pre-Industrial Revolution, average French wage was what percent of the British wage?”

a small crowd of forecasters recruited from the EA and rationality communities very successfully predicted the judgements of a trusted generalist researcher, with a benefit-cost ratio of around 73% compared to the original researcher. They also outperformed a group of external online crowdworkers.

Moreover, we believe this method can be scaled to answer many more questions than a single researcher could, as well as to have application in domains other than research, like grantmaking, hiring and reviewing content.

We preliminarily refer to this method as “amplification” given its similarity to ideas from Paul Christiano’s work on Iterated Distillation and Amplification in AI alignment (see e.g. this).

This was an exploratory project whose purpose was to build intuition for several possible challenges. It covered several areas that could be well suited for more narrow, traditional scientific studies later on. As such, the sample size was small and no single result was highly robust.

However, it did lead to several medium-sized takeaways that we think should be useful for informing future research directions and practical applications.

This post begins with a brief overview of our results. We then share some models of why the current project might be impactful and exciting, followed by some challenges this approach faces.

Overview of the set-up and results

(This section gives a very cursory overview of the set-up and results. A detailed report can be found in this post.)

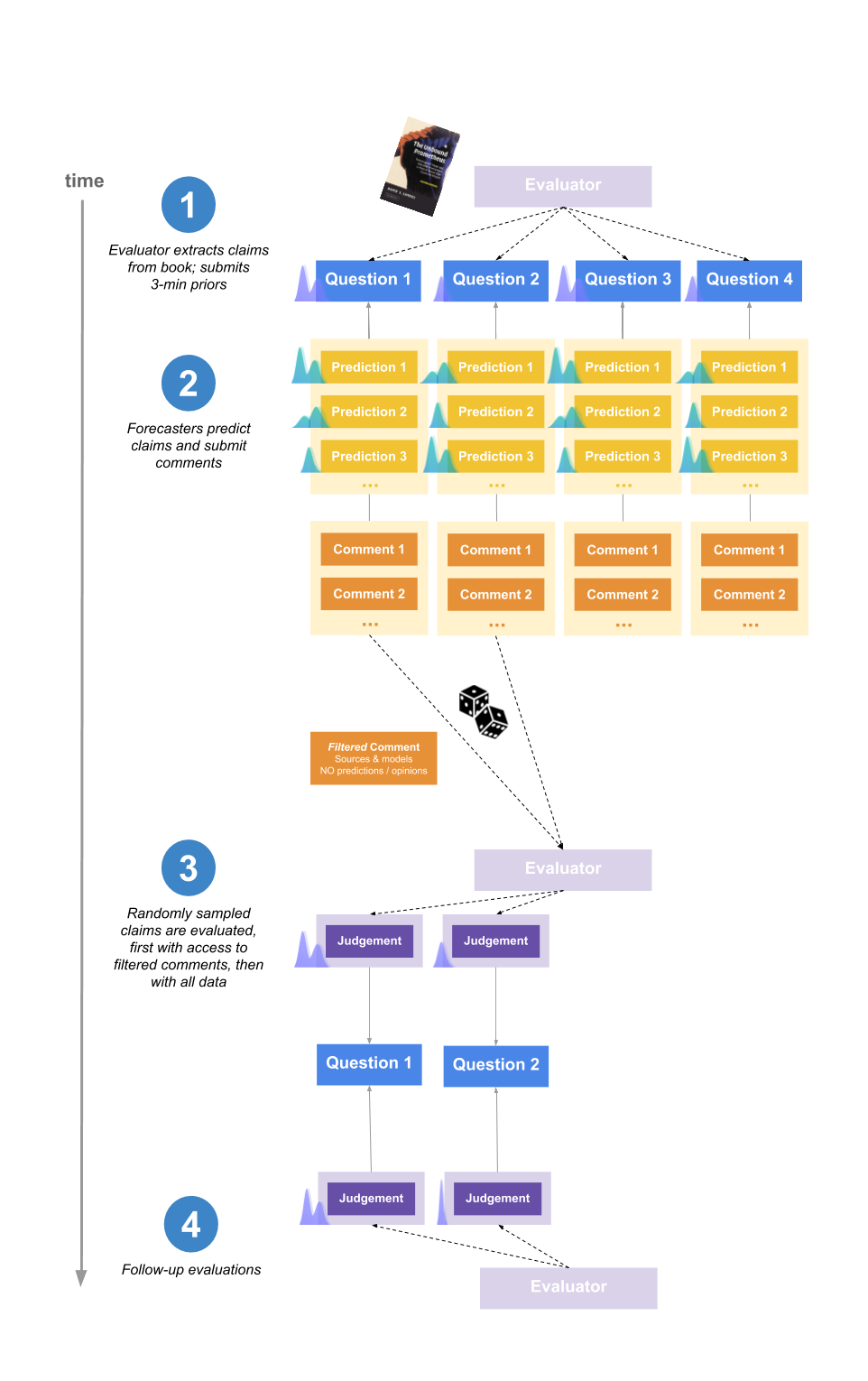

The basic set-up of the project is shown in the following diagram, and described below.

A two-sentence version would be:

Forecasters predicted the conclusions that would be reached by Elizabeth van Norstrand, a generalist researcher, before she conducted a study on the accuracy of various historical claims. We randomly sampled a subset of research claims for her to evaluate, and since we can set that probability arbitrarily low this method is not bottlenecked by her time.

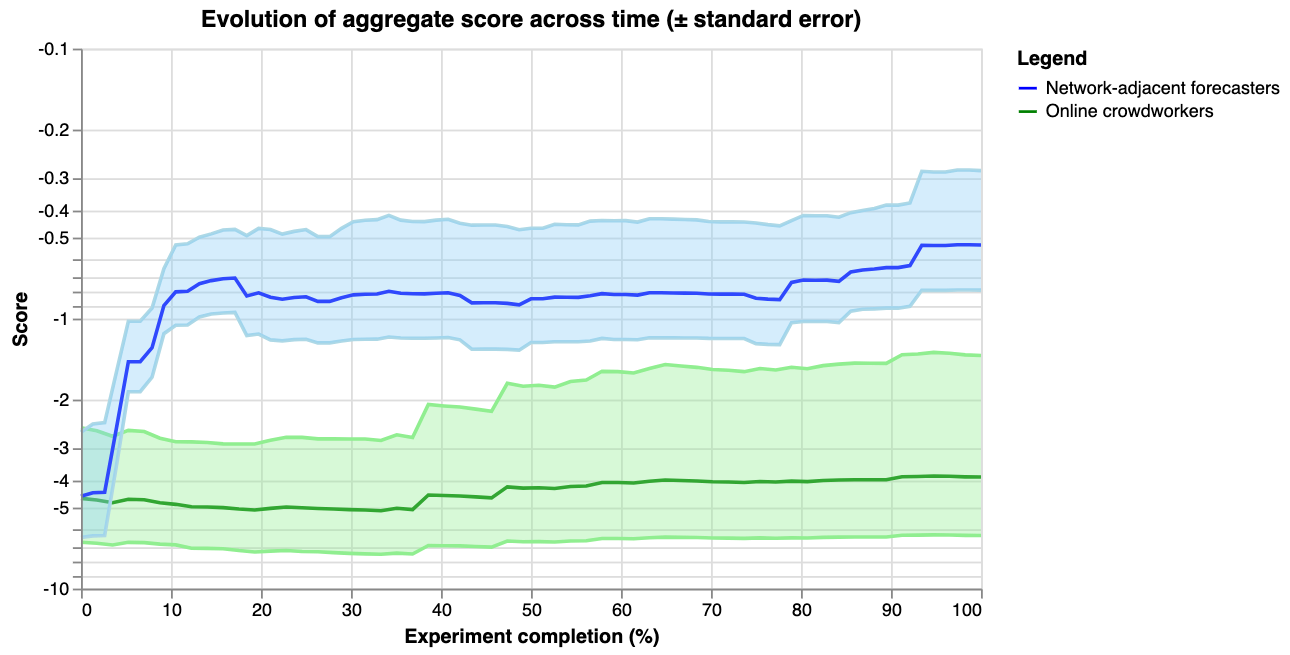

The below graph shows the evolution of the accuracy of the crowd prediction over time, starting from Elizabeth Van Nostrand’s prior. Predictions were submitted separately by two groups of forecasters: one based on a mailing list with participants interested in participating in forecasting experiments (recruited from effective altruism-adjacent events and other forecasting platforms), and one recruited from Positly, an online platform for crowdworkers.

The y-axis shows the accuracy score on a logarithmic scale, and the x-axis shows how far along the experiment is. For example, 14 out of 28 days would correspond to 50%. The thick lines show the average score of the aggregate prediction, across all questions, at each time-point. The shaded areas show the standard error of the scores, so that the graph might be interpreted as a guess of how the two communities would predict a random new question.

One of our key takeaways from the experiment is that our simple algorithm for aggregating predictions performed surprisingly well in predicting Elizabeth’s research output – but only for the network-adjacent forecasters.

Another way to understand the performance of the aggregate is to note that the aggregate of network-adjacent forecasters had an average log score of -0.5. To get a rough sense of what that means, it’s the score you’d get by being 70% confident in a binary event, and being correct (though note that this binary comparison merely serves to provide intuition, there are technical details making the comparison to a distributional setting a bit tricky).

By comparison, the crowdworkers and Elizabeth’s priors had a very poor log score of around -4. This is roughly similar to the score you’d get if you predict an event to be ~5% likely, and it still happens.

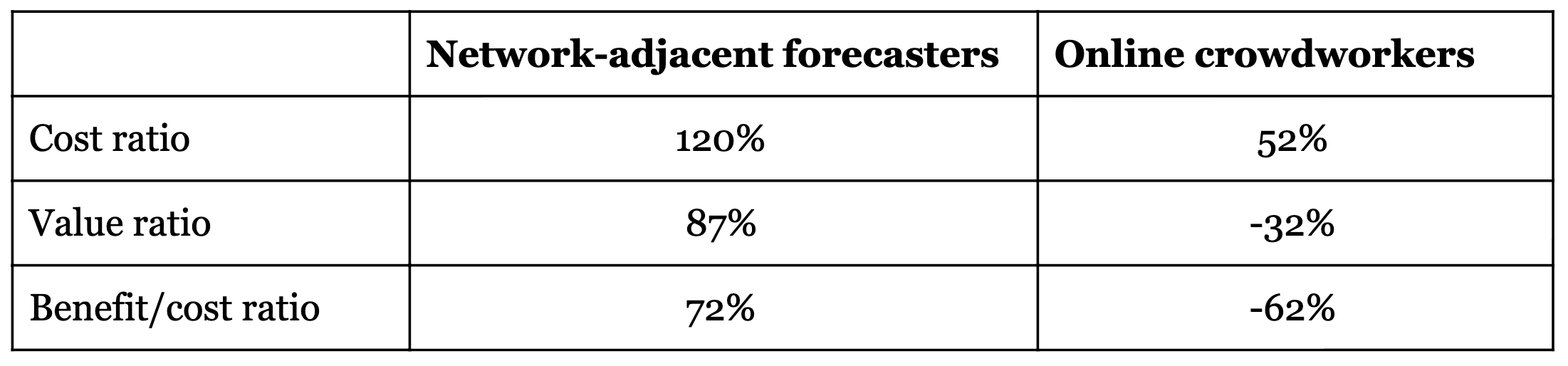

We also calculated a benefit/cost-ratio, as follows:

Benefit/cost ratio = % value provided by forecasters relative to the evaluator / % cost of forecasters relative to the evaluator

We measured “value provided” as the reduction in uncertainty weighted by the importance of the questions on which uncertainty was reduced.

Results were as follows.

In other words, each unit of resource invested in the network-adjacent forecasters provided 72% as much returns as investing it in Elizabeth directly, and each unit invested in the crowdworkers provided negative returns, as they tended to be less accurate than Elizabeth’s prior.

Overall, we tentatively view this as an existence proof of the possibility of amplifying generalist research, and in the future are interested in obtaining more rigorous results and optimising the benefit-cost ratio.

Models of impact

This section summarises some different perspectives on what the current experiment is trying to accomplish and why that might be exciting.

There are several perspectives here given that the experiment was designed to explore multiple relevant ideas, rather than testing a particular, narrow hypothesis.

As a result, the current design is not optimising very strongly for any of these possible uses, and it is also plausible that its impact and effectiveness will vary widely between uses.

To summarise, the models are as follows.

- Mitigating capacity bottlenecks. The effective altruism and rationality communities face rather large bottlenecks in many areas, such as allocating funding, delegating research, vetting talent and reviewing content. The current setup might provide a means of mitigating some of those – a scalable mechanism of outsourcing intellectual labor.

- A way for intellectual talent to build and demonstrate their skills. Even if this set-up can’t make new intellectual progress, it might be useful to have a venue where junior researchers can demonstrate their ability to predict the conclusions of senior researchers. This might provide an objective signal of epistemic abilities not dependent on detailed social knowledge.

- Exploring new institutions for collaborative intellectual progress. Academia has a vast backlog of promising ideas for institutions to help us think better in groups. Currently we seem bottlenecked by practical implementation and product development.

- Getting more data on empirical claims made by the Iterated Amplification AI alignment agenda. These ideas inspired the experiment. (However, our aim was more practical and short-term, rather than looking for theoretical insights useful in the long-term.)

- Exploring forecasting with distributions. Little is known about humans doing forecasting with full distributions rather than point estimates (e.g. “79%”), partly because there hasn’t been easy tooling for such experiments. This experiment gave us some cheap data on this question.

- Forecasting fuzzy things. A major challenge with forecasting tournaments is the need to concretely specify questions; in order to clearly determine who was right and allocate payouts. The current experiments tries to get the best of both worlds – the incentive properties of forecasting tournaments and the flexibility of generalist research in tackling more nebulous questions.

- Shooting for unknown unknowns. In addition to being an “experiment”, this project is also an “exploration”. We have an intuition that there are interesting things to be discovered at the intersection of forecasting, mechanism design, and generalist research. But we don’t yet know what they are.

Mitigating capacity bottlenecks

The effective altruism and rationality communities face rather large bottlenecks in many areas, such as allocating funding, delegating research, vetting talent and reviewing content.

Prediction platforms (for example as used with the current “amplification” set-up) might be a promising tool to tackle some of those problems, for several reasons. In brief, they might act as a scalable way to outsource intellectual labor.

First, we’re using quantitative predictions and scoring rules. This allows several things.

- We can directly measure how accurate each contribution was, and separately measure how useful they were in benefiting the aggregate. The actual calculations are quite simple and with some engineering effort can scale to allocating credit (in terms of money, points, reputation etc.) to hundreds of users in an incentive-compatible way.

- We can aggregate different contributions in an automatic and rigorous way \[3\].

- We have a shared, precise language for interpreting contributions.

Contrast receiving 100 predictions and receiving 20 Google docs. The latter would be prohibitively difficult to read through, does not have a straightforward means of aggregation, and might not even be analysable in an “apples to apples” comparison.

However, the big cost we pay to enable these benefits is that we are adding formalism, and constraining people to express their beliefs within the particular formalism/ontology of probabilities and distributions. We discuss this more in the section on challenges below.

Second, we’re using an internet platform. This makes it easier for people from different places to collaborate, and to organise and analyse their contributions. Moreover, given the benefits of quantification noted above, we can freely open the tournament to people without substantial credentials, since we’re not constrained in our capacity to evaluate their work.

Third, we’re using a mechanism specifically designed to overcome capacity bottlenecks. The key to scalability is that forecasters do not know which claims will be evaluated, and so are incentivised to make their honest, most accurate predictions on all of them. This remains true even as many more claims are added (as long as forecasters expect rewards for participating remain similar).

In effect, we’re shifting the bottleneck from access to a few researchers to access to prize money and competent forecasters. It seems highly implausible that all kinds of intellectual work could be cost-effectively outsourced this way. However, if some work could be outsourced and performed at, say 10% of the quality, but at only 1% of the cost, that could still be very worthwhile. For example, in trying to review hundreds of factual claims, the initial forecasting could be used as an initial, wide-sweeping filter, grabbing the low-hanging fruit; but also identifying which questions are more difficult, and will need attention from more senior researchers.

Overall, this is a model for how things might work, but it is as of yet highly uncertain whether this technique will actually be effective in tackling bottlenecks of various kinds. We provide some preliminary data from this experiment in the “Cost-effectiveness” section below.

A way for intellectual talent to build and demonstrate their skills

The following seems broadly true to some of us:

- Someone who can predict my beliefs likely has a good model of how I think. (E.g. “I expect you to reject this paper’s validity based on the second experiment, but also think you’d change your mind if you thought they had pre-registered that methodology”.)

- Someone who can both predict my beliefs and disagrees with me is someone I should listen to carefully. They seem to both understand my model and still reject it, and this suggests they know something I don’t.

- It seems possible for person X to predict a fair number of a more epistemically competent person Y’s beliefs – even before person X is as epistemically competent as Y. And in that case, doing so is evidence that person X is moving in the right direction.

If these claims are true, we might use some novel versions of forecasting tournaments as a scalable system to identify and develop epistemic talent. This potential benefit looks quite different from using forecasting tournaments to help us solve novel problems or gain better or cheaper information than we could otherwise.

Currently there is no “driver’s license” for rationality or effective altruism. Demonstrating your abilities requires navigating a system of reading and writing certain blog posts, finding connections to more senior people, and going through work trials tailored to particular organisations. This system does not scale very well, and also often requires a social knowledge and ability to “be in the right place at the right time” which does not necessarily strongly correlate with pure epistemic ability.

It seems very implausible that open forecasting tournaments could solve the entire problem here. But it seems quite plausible that it could offer improvements on the margin, and become a reliable credentialing mechanism for a limited class of non-trivial epistemic abilities.

For example, EA student groups with members considering cause prioritisation career paths might organise tournaments where their members forecast the conclusions of OpenPhil write-ups, or maintain and update their own distributions over key variables in GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness models.

By running this experiment, writing up the results, and improving the Foretold platform, we hope to provide infrastructure that will allow others interested in this benefit to run their own experiments.

Exploring new institutions for collaborative intellectual progress

Many of our current most important institutions, like governments and universities, run on mechanisms designed hundreds of years ago, before fields like microeconomics and statistics were developed. They suffer from many predictable and well-understood incentive problems, such as poor replication rates of scientific findings following from a need to optimise for publications; the election of dangerous leaders due to the use of provably suboptimal voting systems; or the failure to adequately fund public goods like high-quality explanations of difficult concepts due to free-rider problem, just to name a few.

The academic literature in economics and mechanism design has a vast backlog of designs for new institutions that could solve these and other problems. One key bottleneck now seems to be implementation.

For example, ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin has argued that the key skill required is product development: making novel mechanisms with better incentives work in practice (search for “product people” in linked interview).

Similarly, Robin Hanson has argued that there is a large, promising literature on more effective institutions, but “what we need most \[... is lots of concrete trials.\] To get involved in the messy details of an organization, and just try out different variations until \[we\] see something that actually works” \[4\], \[5\].

Part of the spirit of the current experiment is an attempt to do just this, and, in particular, to do so in the domain of research intellectual progress.

Getting more data on empirical claims made by the Iterated Amplification AI alignment agenda

The key mechanism underlying this experiment, and its use of prediction and randomisation, is based on ideas from the Iterated Amplification approach to AI alignment. Currently groups at Ought, OpenAI and elsewhere are working on testing the empirical assumptions underlying that theory.

Compared to these groups, the current experiment had a more practical, short-term aim – to find a “shovel-ready” method of amplifying generalist research, that could be applied to make the EA/rationality communities more effective already over the coming years.

Nonetheless, potential follow-ups from this experiment might provide useful theoretical insight in that direction.

Exploring forecasting with distributions

Little is known about doing forecasting with full distributions (e.g. “I think this is captured by two normals, with means 5 and 10 and variance 3”) rather than point estimates (e.g. “79%”). Before the launch of Foretold, there wasn’t any software available for easily running such experiments.

This was a quick way of getting data on many questions in distributional forecasting:

- How good are humans at it?

What are the main usability challenges?

In terms of intuitive scoring rules?

In terms of intuitive yet powerful input formats?

What are best practices? (For example, using beta rather than lognormal distributions when forecasting someone else’s prediction, or averaging distributions with a wide uniform to hedge against large losses)

Forecasting fuzzy things

A major challenge with prediction markets and forecasting tournaments is the need to concretely specify questions; in order to clearly determine who was right and allocate payouts.

Often, this means that these mechanisms are limited to answering questions like:

“What will the highest performance of an algorithmic benchmark x be at time t?”

Even though what we often care about is something more nebulous, like:

“How close will we be to AGI at time t?”

The upside of this precision is that it enables us to use quantitative methods to estimate performance, combine predictions, and allocate rewards, as described above.

The current experiments try to get the best of both worlds: the incentive properties of forecasting tournaments and the flexibility of generalist research in tackling more nebulous questions. The proposed solution to this problem is simply to have one or many trusted evaluators who decide on the truth of a question, and then predict their judgements as opposed to the underlying question \[6\].

(Previously some of the authors set up the AI Forecasting Resolution Council to enable such flexible resolution to also be used on AI questions.)

Shooting for unknown unknowns

This is related to the mindset of “prospecting for gold”. To a certain extent, we think that we have a potentially reliably inside view, a certain research taste which is worth following and paying attention to, because we are curious what we might find out.

A drawback with this is that it enables practices like p-hacking/publication bias if results are reported selectively. To mitigate this, all data from this experiment is publicly available here \[7\].

Challenges

This section discusses some challenges and limitations of the current exploration, as well as our ideas for solving some of them. In particular, we consider:

- Complexity and unfamiliarity of experiment. The current experiment had many technical moving parts. This makes it challenging to understand for both participants and potential clients who want to use it in their own organisations.

- Trust in evaluations. The extent to which these results are meaningful depends on your trust in Elizabeth Van Nostrand’s ability to evaluate questions. We think is partly an inescapable problem, but also expect clever mechanisms and more transparency to be able to make large improvements.

- Correlations between predictions and evaluations. Elizabeth had access to a filtered version of forecaster comments when she made her evaluations. This introduces a potential source of bias and a “self-fulfilling prophecy” dynamic in the experiments.

- Difficulty of converting mental models into quantitative distributions. It’s hard to turn nuanced mental models into numbers. We think a solution is to have a “division of labor”, where some people just build models/write comments and others focus on quantifying them. We’re working on incentive schemes that work in this context.

- Anti-correlation between importance and “outsourceability”. The intellectual questions which are most important to answer might be different from the ones that are easiest to outsource, in a way which leaves very little value on the table in outsourcing.

- Overhead of question generation. Creating good forecasting questions is hard and time-consuming, and better tooling is needed to support this.

- Scoring rule that discourages collaboration. Prediction markets and tournaments tend to be zero-sum games, with negative incentives for helping other participants or sharing best practices. To solve this we’re designing and testing improved scoring rules which directly incentivise collaboration.

Complexity and unfamiliarity of experiment.

The current experiment has many moving parts and a large inferential distance. For example, in order to participate, one would need to understand the mathematical scoring rule, the question input format, the randomisation of resolved questions and how questions would be resolved as distributions.

This makes the set-up challenging to understand to both participants and potential clients who want to use similar amplification set-ups in their own organisations.

We don’t think these things are inherently complicated, but have much work to do on explaining the set-up and making the app generally accessible.

Trust in evaluations.

The extent to which the results are meaningful depends on one’s trust in Elizabeth Van Nostrand’s ability to evaluate questions. We chose Elizabeth for the experiment as she has a reputation for reliable generalist research (through her blog series on “Epistemic Spot Checks”), and 10+ public blog posts with evaluations of the accuracy of books and papers.

However, the challenge is that this trust often relies on a long history of interactions with her material, in a way which might be hard to communicate to third-parties.

For future experiments, we are considering several improvements here.

First, as hinted at above, we can ask forecasters both about their predictions of Elizabeth as well as their own personal beliefs. We might then expect that those who can both accurately predict Elizabeth and disagree with her knows something she does not, and so will be weighted more highly in the evaluation of the true claim.

Second, we might have set-ups with multiple evaluators; or more elaborate ways of scoring the evaluators themselves (for example based on their ability to predict what they themselves will say after more research).

Third, we might work to have more transparent evaluation processes, for example including systematic rubrics or detailed write-ups of reasoning. We must be careful here not to “throw out the baby with the bathwater”. The purpose of using judges is after all to access subjective evaluations which can’t be easily codified in concrete resolution conditions. However, there seems to be room for more transparency on the margin.

Correlation between predictions and evaluations.

Elizabeth had access to a filtered version of forecaster comments when she made her evaluations. Hence the selection process on evidence affecting her judgements was not independent from the selection process on evidence affecting the aggregate. This introduces a potential source of bias and a “self-fulfilling prophecy” dynamic of the experiments.

For future experiments, we’re considering obtaining an objective data-set with clear ground truth, and test the same set-up without revealing the comments to Elizabeth, to get data on how serious this problem is (or is not).

Difficulty of converting mental models into quantitative distributions.

In order to participate in the experiment, a forecaster has to turn their mental models (represented in whichever way the human brain represents models) into quantitative distributions (which is a format quite unlike that native to our brains), as shown in the following diagram:

Each step in this chain is quite challenging, requires much practice to master, and can result in a loss of information.

Moreover, we are uncertain how the difficulty of this process differs across questions of varying importance. It might be that some of the most important considerations in a domain tend to be confusion-shaped (e.g. “What does it even mean to be aligned under self-improvement when you can’t reliably reason about systems smarter than yourself?”), or very open-ended (e.g. “What new ideas could reliably improve the long-term future?” rather than “How much will saving in index funds benefit future philanthropists?”)). Hence filtering for questions that are more easily quantified might select against questions that are more important.

Consider some solutions. For the domains where quantification seems more promising, it seems at least plausible that there should be possible to have some kind of “division of labor” between them.

For future experiments, we’re looking to better separate “information contribution” and “numerical contribution”, and find ways of rewarding both. Some participants might specialise in research or model-generation, and others in turning that research into distributions.

A challenge here is to appropriately reward users who only submit comments but do not submit predictions. Since one of the core advantages of forecasting tournaments is that they allow us to precisely and quantitatively measure performance, it seems plausible that any solution should try to make use of this fact. (As opposed to, say, using an independent up- and downvoting scheme.) As example mechanisms, one might randomly show a comment to half the users, and reward a comment based on the performance of the aggregate for users who’ve seen it and users who haven’t. Or one might release the comments to forecasters sequentially, and see how much each improves the aggregate. Or one might simply allow users to vote, but weigh the votes of users with a better track-record higher.

Moreover, in future experiments with Elizabeth we’ll want to pair her up with a “distribution buddy”, whose task is to interview her to figure out in detail what distribution best captures her beliefs, allowing Elizabeth to focus simply on building conceptual models.

Anti-correlation between importance and “outsourceability”

Above we mentioned that the questions easiest to quantify might be anti-correlated with the ones that are most important. It is also plausible that the questions which are easiest to outsource to forecasters are not the same as those which are most important to reduce uncertainty on. Depending on the shape of these distributions, the experiment might not be capture a lot of value. (For illustration, consider an overly extreme example: suppose a venture capitalist tries to amplify their startup investments. The crowd always predicts “no investment”, and turn out to be right in 99/100 cases: the VC doesn’t investment. However, the returns for that one case where crowd fails and the VC actually would have invested by far dominate the portfolio.)

Overhead of question generation.

The act of creating good, forecastable questions is an art in and of itself. If done by the same person or small team which will eventually forecast the questions, one can rely on much shared context and intuition in interpreting the questions. However, scaling these systems to many participants requires additional work in specifying the questions sufficiently clearly. This overhead might be very costly. Especially since we think one of the key factors determining the usefulness of a forecasting question is the question itself. How well does it capture something we care about? From experience, writing these questions is hard. In future we have much work to do to make this process easier.

A scoring rule that discourages collaboration

Participants were scored based on how much they outperformed the aggregate prediction. This scoring approach is similar to the default in prediction markets and major forecasting tournaments. It has the problem that sharing any information via commenting will harm your score (since it will make the performance of other users, and hence the aggregate, better). What’s more, all else remaining the same, doing anything that helps other users will be worse for your score (such as sharing tips and tricks for making better predictions, or pointing out easily fixable mistakes so they can learn from them).

There are several problems with this approach and how it a disincentives collaboration.

First, it provides an awkward change in incentives for groups who otherwise have regular friendly interactions (such as a team at a company, a university faculty, or members of the effective altruism community).

Second, it causes effort to be wasted as participants must derive the same key insights individually, utilising little division of labor (as any sharing information will just end up hurting their score on the margin). Having some amount of duplication of work and thinking can of course make the system robust against mistakes – but we think the optimal amount is far less than the equilibrium under the current scoring rule.

In spite of these theoretical incentives, it is interesting to note that several participants actually ended up writing detailed comments. (Though basically only aimed at explaining their own reasoning, with no collaboration and back-and-forth between participants observed.) This might have been because they knew Elizabeth would see those comments, or for some other reason.

Nonetheless, we are working on modifying our scoring rule in a way which directly incentivises participants to collaborate, and actively rewards helping other users improve their models. We hope to release details of formal models and practical experiments in the coming month.

Footnotes

\[1\] Examples include: AI alignment, global coordination, macrostrategy and cause prioritisation.

\[2\] We chose the industrial revolution as a theme since it seems like a historical period with many lessons for improving the world. It was a time of radical change in productivity along with many societal transformations, and might hold lessons for future transformations and our ability to influence those.

\[3\] For example by averaging predictions and then weighing by past track-record and time until resolution, as done in the Good Judgement Project (among other things).

\[4\] Some examples of nitty-gritty details we noticed while doing this are:

- Payoffs were too small/the scoring scheme too harsh

- Copying the aggregate to your distributions and then just editing a little was something natural, so we added support in the syntax for writing =multimodal(AG, your prediction)

- Averaging with a uniform would have improved predictions.

- The marginal value of each additional prediction was low after the beginning.

- Forecasters were mostly motivated by what questions were interesting, followed by what would give them a higher payout, and less by what would be most valuable to the experimenters.

\[5\] For a somewhat tangential, but potentially interesting, perspective, see Feynman on making experiments to figure out nitty-gritty details in order to enable other experiments to happen (search for “rats” in the link).

\[6\] A further direction we’re considering is to allow forecasters to both predict the judgements of evaluators and the underlying truth. We might then expect that those predictors who both accurately forecast the judgement of the evaluator and disagree in their own judgements, might provide valuable clues about the truth.

\[7\] For the record, before this experiment we ran two similar, smaller experiment (to catch easy mistakes and learn more about the set up), with about an order of magnitude less total forecasting effort invested. The aggregate from these experiments was quite poor at predicting the evaluations. The data from those experiments can be found here, and more details in Elizabeth’s write-ups here and here.

Participate in future experiments or run your own

Foretold.io was built as an open platform to enable more experimentation with prediction-related ideas. We have also made data and analysis calculations from this experiment publicly available.

If you’d like to:

- Run your own experiments on other questions

- Do additional analysis on this experimental data

- Use an amplification set-up within your organisation

We’d be happy to consider providing advice, operational support, and funding for forecasters. Just comment here or reach out to this email.

If you’d like to participate as a forecaster in future prediction experiments, you can sign-up here.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the Berkeley Existential Risk Initiative and the EA Long-term Future Fund.

We thank Beth Barnes and Owain Evans for helpful discussion.

We are also very thankful to all the participants.