An experiment to evaluate the value of one researcher’s work

Introduction

EA has lots of small research projects of uncertain value. If we improved our ability to assess value, we could redistribute funding to more valuable projects after the fact (e.g. using certificates of impact), or start to build forecasting systems which predict their value beforehand, and then choose to carry out the most valuable projects.

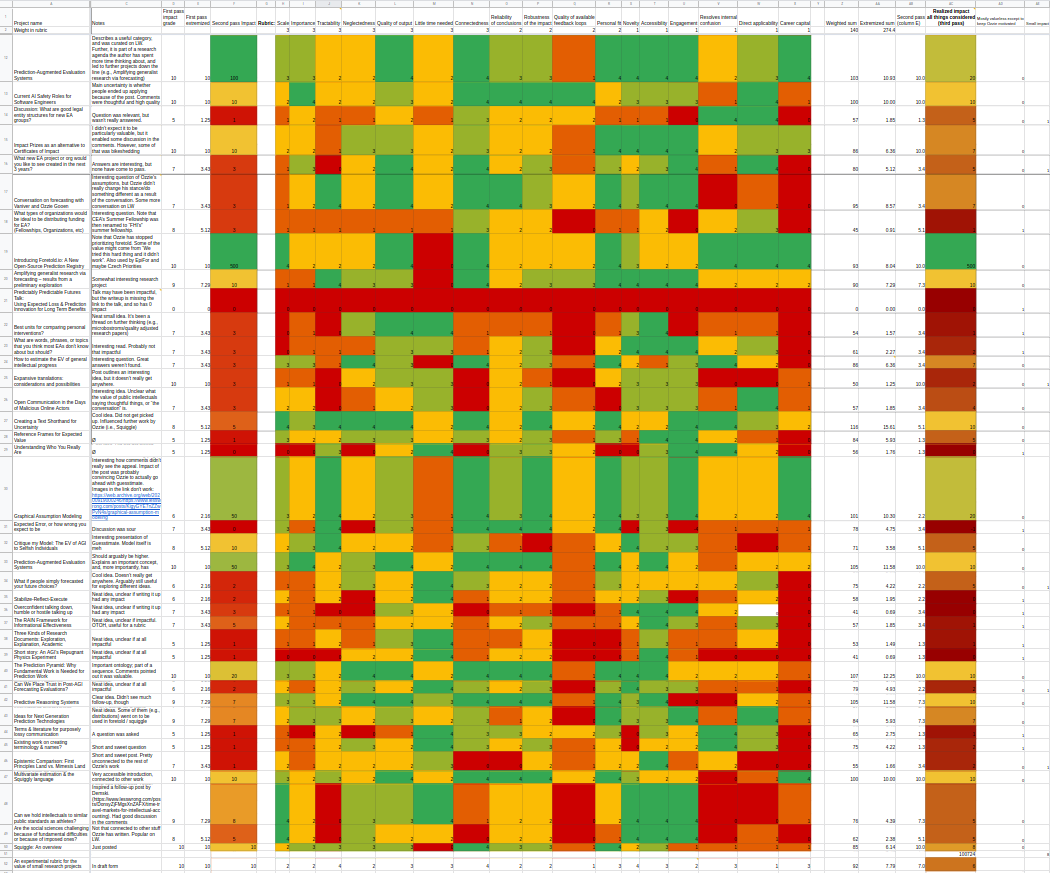

With the goal of understanding how difficult it is to assess the value of research after the fact, I went through all of Ozzie Gooen’s research output in the EA forum and on LessWrong, using an ad-hoc rubric. I’d initially asked more authors, but I found that Ozzie was particularly accessible and agreeable, and he already had a large enough number of posts for a preliminary project.

As my primary conclusion, I found that assessing the relative value of projects was doable. I was also left with the impression that Ozzie’s work is divided between, on the one hand, a smaller number of projects that build upon one another and that seem fairly valuable, and on the other hand a larger number of posts which don’t seem to have brought about much value and aren’t related to any other posts before or after.

The reader can see my results here, though I’d like to note that they’re preliminary and experimental, as is the rest of this post. Towards the end of this post, there is a section which mentions more caveats.

Related work:

- Charity Entrepreneurship’s beautiful weighted factor model

- Prediction Augmented Evaluation Systems

- Predicting the Value of Small Altruistic Projects: A Proof of Concept Experiment

Thanks to Ozzie Gooen and Elizabeth Van Nostrand for thoughtful comments, and to Ozzie Gooen for suggesting the project.

Method

I rated each project using two distinct methods. First, I rated each project using my holistic intuition, taking care that their relative values made preliminary sense (i.e., that I’d be willing to exchange one project worth n units for k projects worth n/k units.) I then rated them with a rubric, using a 0-4 Likert scale for each of the rubric’s elements. I then combined each rubric score with my intuition to come up with a final estimate of expected value, paying particular attention to the projects for which the rubric score and my intuition initially produced different answers.

Rubric elements

I produced this rubric by babbling, and by borrowing from previous rubrics I knew about, seeking to not spend too much time on its design. Note that the rubric contains many elements, whereas a final rubric would perhaps contain fewer. Here is a more cleaned up and easier to read — yet still very experimental — version of the rubric, though not exactly the one I used.

- Scale: Does this project affect many people?

- Importance: How important is the issue for the people affected?

- Tractability: How likely is the project to succeed in its goals?

- Neglectedness: How neglected is the area in which this project focuses on?

- Reliability: How much can we trust the conclusions of the project?

- Robustness: Is the project likely to be a good idea under many different models? Are there any models under which this project has a value of 0 or net negative?

- Novelty: Are the ideas presented novel? Is this project pursuing a novel direction?

- Accessibility: How understandable is this project to a motivated reader?

- Time needed: How long did it take to write the post? How long did it take to carry out the project of which the post is a write up?

- Quality of feedback-loops available: Will the authors know if it the project is going wrong?

- Quality of output.

- Connectedness: Is this project related to previous work? Does it inspire future work? Is this project part of a concerted effort to solve a larger problem?

- Engagement: Does this project elicit positive and constructive comments from casual readers? Is this project upvoted a lot?

- Resolves internal confusion: Does this project resolve any of the author’s personal confusions? Is its value of information high?

- Direct applicability: Is this project directly applicable to making the world better, or does it require many steps until impact is realized?

- Career capital: Does this project generate career capital for the one who carries it out?

- Personal fit: Was the project a good personal fit for the author?

In hindsight,

- Some of the elements of the rubric didn’t really match up with research oriented projects, e.g., it’s difficult to say whether theorizing about the shape of Predictive Systems is tractable (it’s in general hard to estimate the tractability of a research direction before the fact.)

- It’s not clear what the a priori probability of success of a project which ultimately succeeded is.

- Although most of the projects I looked into probably didn’t generate much career capital, maybe many together did.

- I might have wanted to borrow heavily from Charity Entrepreneurship’s rubric, but I did want to see what I could come up with on my own.

Unit: Quality Adjusted Research Papers

My arbitrary and ad-hoc unit was a “Quality Adjusted Research Paper” (QARP). For illustration purposes:

- ~0.1-1 mQ: A particularly thoughtful blog post comment, like this one

- ~10 mQ: A particularly good blog post, like Extinguishing or preventing coal seam fires is a potential cause area

- ~100 mQ: A fairly valuable paper, like Categorizing Variants of Goodhart’s Law.

- ~1Q: A particularly valuable paper, like The Vulnerable World Hypothesis

- ~10-100 Q: The Global Priorities Institute’s Research Agenda.

- ~100-1000+ Q: A New York Times Bestseller on a valuable topic, like Superintelligence (cited 2,651 times), or Thinking Fast and Slow (cited 30,439 times.)

- ~1000+ Q: A foundational paper, like Shannon’s “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” (cited 131,736 times.)

This spans six orders of magnitude (1 to 1,000,000 mQ), but I do find that my intuitions agree with the relative values, i.e., I would probably sacrifice each example for 10 equivalents of the preceding type (and vice-versa).

Throughout, a unit — even if it was arbitrary or ad-hoc — made relative comparison easier, because instead of comparing all the projects with each other, I could just compare them to a reference point. It also made working with different orders of magnitude easier: instead of asking how valuable a blog post is compared to a foundational paper I could move up and down in steps of 10x, which was much more manageable.

Example: Rating this project using its own rubric

The last row of the results rates this project. It initially gets a 10 mQ based on my holistic intuition (connected to previous work, takes relatively little time, resolves some of my internal confusions, etc.) But after seeing that my rubric gives it a 7.5 mQ and looking at other projects, I downgraded this to a 6 mQ, i.e., between What if people simply forecasted your future choices? (5) and Ideas for Next Generation Prediction Technologies (7).

Technical details: aggregation and extremizing

The problem of aggregating the elements of a rubric felt to me to be multiplicative, rather than additive. That is, I think that the value of a project looks more like

Scale * Tractability * Neglectedness * ...

or

Number of people affected * Probability of Success * Probability problem would have been solved anyways * ...

than like

Scale+Tractability+Neglectedness+...

or like

Number of people affected+Probability of Success+Probability problem would have been solved anyways+...

Further, I also had the sense that for these variables, my brain thinks logarithmically. That is, I don’t perceive Scale, Tractability, Neglectedness, I perceive something closer to log(Scale), log(Tractability), log(Neglectedness).

| What I perceive | What I care about | How it’s aggregated |

|---|---|---|

| log(Scale) | Scale | Total value ~ Scale*Tractability*Neglectedness* ... |

Thus, I was planning to exponentiate the sum of the (weighted) rubric variables, because

Scale * Tractability * Neglectedness * ... = exp{log(Scale)+log(Tractability)+log(Neglectedness) + log(...)}

These variables would then be weighted, so that introducing a less important variable, like, say, novelty, would translate to

Scale * Tractability * Neglectedness * sqrt(Novelty) = exp{log(Scale)+log(Tractability)+log(Neglectedness) + 0.5* log(Novelty)}

which in my mind made sense. Sadly, this did not work out, that is, aggregating Likert ratings that way didn’t produce a result which matched with my intuitions.

I tried different transformations, and in the end, one which did somewhat match my intuitions was s→100∗(s/100)3, where s is the sum of the rubric variables (in our previous example, s\=log(Scale)+log(Tractability)+log(Neglectedness)+… and the transformation wass→exp{s}). This produced relative values which made sense to me, and were normalized such that 10 Q was roughly equal to a particularly good EA forum post.

I think that the theoretically elegant part of that transformation is that it will still be correlated with impact, but will give different errors than my intuition, so that combining them with my intuition will produce a more accurate picture.

A different alternative might have been to simply add up the z scores (subtract the mean, divide by the standard deviation), which is the solution used by Charity Entrepreneurship.

Another approach might have been to try to actually consider the multiplicative factors for each element in the rubric. For example, one could have units that naturally multiply together, like importance for each person affected (in e.g., QALYs), number of people, and probability of success (0 to 100%). When one multiplies these together, one gets total expected QALYs. In any case, this gets complicated quickly as one adds more elements to a rubric.

Results and comments.

The reader can see the results here. My main takeaways are:

Many projects don’t seem to have brought about much value

Many projects don’t seem to have brought about much value, and might have been valuable only to the extent that they helped the author keep motivated. Some examples to which I gave very low scores are here, here, here, and in general I/the rubric gave many projects a fairly low score. Ozzie comments:

One obvious question that comes from this is a difference between expected value and apparent value. It could be the case that the expected value of these tiny things were quite high because they were experimental. New posts in areas outside of an author’s main area might have a small probability of becoming the authors next main area.

Further, though these posts were higher in number, they might have comprised a lower proportion of total research time than more time intensive projects.

Lastly, this conclusion is lightly held. For example, Ozzie gives a higher value to Can We Place Trust in Post-AGI Forecasting Evaluations? than either myself or the rubric did, and given that he’s spent more time thinking about it that I did, it wouldn’t surprise me if he was right.

Being part of a concerted effort was important

Projects which seemed valuable to me usually belonged to a cluster, either Prediction Systems or the more recent Epistemic Progress. Despite often not having that much engagement in the comments, Ozzie has kept working on them based on personal intuition.

In particular, consider Graphical Assumption Modeling (archive link with images) and Creating a Text Shorthand for Uncertainty, which outlined what would later become Guesstimate. These posts had few upvotes, and the comments are broadly positive but not that informative, and bike-shed a lot. A similar example of a valuable project (by another author) which was only recognized as such after the fact is Fundraiser: Political initiative raising an expected USD 30 million for effective charities (which went on to become EAF’s ballot initiative doubled Zurich’s development aid). Although both examples are the product of a selection effect, this marginally increases the weight I give to personal intuition vs people’s opinions.

There was also a cluster of “community building” posts, whose impact was harder to evaluate. However, at least one of them seemed fairly valuable, namely Current AI Safety Roles for Software Engineers.

Overall I’d give a lot of weight to “connectedness”, i.e., whether a project is part of a concerted effort to solve a given problem, as opposed to a one-shot. The post Extinguishing or preventing coal seam fires is a potential cause area does really poorly in this area, because although it prepares the ground for e.g., a coal seam fires charity, the idea wasn’t picked up; there was no follow-up.

The most valuable project seems to outweigh everything else combined

Guesstimate so far seems to outweigh every other project in the list together, with an estimated value of ~10-100+ Q. This is similar in magnitude to how valuable I think The Global Priorities Institute’s Research Agenda is, though given that my reference unit is 10 mQ, I’m very uncertain. I arrived at this by attempting to guess the average value (in Q) of each Guesstimate model, of which there are currently 17k+ (Guesstimate model here). If we take out Guesstimate, the next more valuable project, Foretold, also outweighs everything else combined.

As an aside, Ozzie also has a meta-project, something like “building expertise in predictive systems”, and a community around it, which I’d rate more valuable than Foretold, but which didn’t have a clear post to assign to. More generally, I’d imagine that not all of Ozzie’s research is captured in his posts.

Caveats and warnings

As I was writing this project, Ozzie left some thoughtful comments emphasizing the uncertainty intrinsic in this kind of project. I could have adopted them into the main text, but then I’d wonder whether I would have used less caveats if the results had been different, so instead I reproduce them below:

I also would suggest stressing/acknowledging the messiness he goes into the sort of work. I think we should be pretty uncertain about the results of this, and if it seems to readers that we’re not, that seems bad. Generally rubrics in similar instill overconfidence in readers, from what I’ve seen in this area before.

So far in this document it sounds like you could be expecting this to be a perfectly final measure, and I don’t think that’s the case. For example you edit so many rubric elements arguably in large part as an experiment for future better rubrics.

This \[that many projects don’t seem to have brought about much value, originally worded as "most projects are fairly valueless"\] seems like a pretty bold statement given the relatively short amount of time it took for this piece. It doesn’t seem like you’ve done any empirical work, for example, going out in the world and interviewing people about the results.

I’m fine with you suggesting bold things but it should be really clear that they aren’t definitive. I really don’t like overconfidence and I’m also worried about people thinking that you’re overconfident.

Even if it’s clear to you that you mean a lot of this with uncertainty, it seems common that readers don’t pick up on that, So we need to be extra cautious.

One obvious question that comes from this is a difference between expected value and apparent value. It could be the case that the expected value of these tiny things were quite high because they were experimental. New posts in areas outside of an author’s main area might have a small probability of becoming the authors next main area.

I would suggest thanking or at least mentioning that I reviewed this and gave feedback, both because I did and because it’s about me, so I feel like readers might find it important to know. It is also in part a disclaimer that this work may have been a bit biased because of it.

Conclusion

Ideally, we would want to think in terms of the amount of, say, utilons, for each intervention, and have objective currency conversion between different cause areas, such as human and animal welfare. We’d also want perfect foresight to determine the expected utilons for each project. Absent that, I’ll settle for one unit for each cause area (QALYs, tonnes of CO2 emitted, QARPs, etc), uncertain probabilistic currency conversion, and imperfect yet really good forecasting systems.

Future work

I’ve asked several people if I could use their posts, and several said yes, with the common sentiment being that they are already being rated in terms of upvotes. If you wouldn’t mind your own posts being rated as well, do leave a comment!

In private conversation, Ozzie makes the point that better evaluation systems might be the solution to some coordination systems. For example, if we could measure the value of projects better we could assign status more directly to those who carry out more valuable projects, or directly only implement the most valuable projects. But the case for better evaluation systems does need to be made.

Lastly, there is of course work to be done to improve the ad-hoc rubric in this post (see here for my current version). For this, examples of past rubrics might prove useful; see Prize: Interesting Examples of Evaluations if you have any suggestions.