My highly personal skepticism braindump on existential risk from artificial intelligence.

Summary

This document seeks to outline why I feel uneasy about high existential risk estimates from AGI (e.g., 80% doom by 2070). When I try to verbalize this, I view considerations like

- selection effects at the level of which arguments are discovered and distributed

- community epistemic problems, and

- increased uncertainty due to chains of reasoning with imperfect concepts

as real and important.

I still think that existential risk from AGI is important. But I don’t view it as certain or close to certain, and I think that something is going wrong when people see it as all but assured.

Discussion of weaknesses

I think that this document was important for me personally to write up. However, I also think that it has some significant weaknesses:

- There is some danger in verbalization leading to rationalization.

- It alternates controversial points with points that are dead obvious.

- It is to a large extent a reaction to my imperfectly digested understanding of a worldview pushed around the ESPR/CFAR/MIRI/LessWrong cluster from 2016-2019, which nobody might hold now.

In response to these weaknesses:

- I want to keep in mind that I do want to give weight to my gut feeling, and that I might want to update on a feeling of uneasiness rather than on its accompanying reasonings or rationalizations.

- Readers might want to keep in mind that parts of this post may look like a bravery debate. But on the other hand, I’ve seen that the points which people consider obvious and uncontroversial vary from person to person, so I don’t get the impression that there is that much I can do on my end for the effort that I’m willing to spend.

- Readers might want to keep in mind that actual AI safety people and AI safety proponents may hold more nuanced views, and that to a large extent I am arguing against a “Nuño of the past” view.

Despite these flaws, I think that this text was personally important for me to write up, and it might also have some utility to readers.

Uneasiness about chains of reasoning with imperfect concepts

Uneasiness about conjunctiveness

It’s not clear to me how conjunctive AI doom is. Proponents will argue that it is very disjunctive, that there are lot of ways that things could go wrong. I’m not so sure.

In particular, when you see that a parsimonious decomposition (like Carlsmith’s) tends to generate lower estimates, you can conclude:

- That the method is producing a biased result, and trying to account for that

- That the topic under discussion is, in itself, conjunctive: that there are several steps that need to be satisfied. For example, “AI causing a big catastrophe” and “AI causing human exinction given that it has caused a large catastrophe” seem like they are two distinct steps that would need to be modelled separately,

I feel uneasy about only doing 1.) and not doing 2.) I think that the principled answer might be to split some probability into each case. Overall, though, I’d tend to think that AI risk is more conjunctive than it is disjunctive

I also feel uneasy about the social pressure in my particular social bubble. I think that the social pressure is for me to just accept Nate Soares’ argument here that Carlsmith’s method is biased, rather than to probabilistically incorporate it into my calculations. As in “oh, yes, people know that conjunctive chains of reasoning have been debunked, Nate Soares addressed that in a blogpost saying that they are biased”.

I don’t trust the concepts

My understanding is that MIRI and others’ work started in the 2000s. As such, their understanding of the shape that an AI would take doesn’t particularly resemble current deep learning approaches.

In particular, I think that many of the initial arguments that I most absorbed were motivated by something like an AIXI (Somolonoff induction + some decision theory). Or, alternatively, by imagining what a very buffed-up Eurisko would look like. This seems to be like a fruitful generative approach which can generate things that could go wrong, rather than demonstrating that something will go wrong, or pointing to failures that we know will happen.

As deep learning attains more and more success, I think that some of the old concerns port over. But I am not sure which ones, to what extent, and in which context. This leads me to reduce some of my probability. Some concerns that apply to a more formidable Eurisko but which may not apply by default to near-term AI systems:

- Alien values

- Maximalist desire for world domination

- Convergence to a utility function

- Very competent strategizing, of the “treacherous turn” variety

- Self-improvement

- etc.

Uneasiness about in-the-limit reasoning

One particular form of argument, or chain of reasoning, goes like:

- An arbitrarily intelligent/capable/powerful process would be of great danger to humanity. This implies that there is some point, either at arbitrary intelligence or before it, such that a very intelligent process would start to be and then definitely be a great danger to humanity.

- If the field of artificial intelligence continues improving, eventually we will get processes that are first as intelligent/capable/powerful as a single human mind, and then greatly exceed it.

- This would be dangerous

The thing is, I agree with that chain of reasoning. But I see it as applying in the limit, and I am much more doubtful about it being used to justify specific dangers in the near future. In particular, I think that dangers that may appear in the long-run may manifest in limited and less dangerous form in earlier on.

I see various attempts to give models of AI timelines as approximate. In particular:

- Even if an approach is accurate at predicting when above-human level intelligence/power/capabilities would arise

- This doesn’t mean that the dangers of in-the-limit superintelligence would manifest at the same time

AGI, so what?

For a given operationalization of AGI, e.g., good enough to be forecasted on, I think that there is some possibility that we will reach such a level of capabilities, and yet that this will not be very impressive or world-changing, even if it would have looked like magic to previous generations. More specifically, it seems plausible that AI will continue to improve without soon reaching high shock levels which exceed humanity’s ability to adapt.

This would be similar to how the industrial revolution was transformative but not that transformative. One possible scenario for this might be a world where we have pretty advanced AI systems, but we have adapted to that, in the same way that we have adapted to electricity, the internet, recommender systems, or social media. Or, in other words, once I concede that AGI could be as transformative as the industrial revolution, I don’t have to concede that it would be maximally transformative.

I don’t trust chains of reasoning with imperfect concepts

The concerns in this section, when combined, make me uneasy about chains of reasoning that rely on imperfect concepts. Those chains may be very conjunctive, and they may apply to the behaviour of an in-the-limit-superintelligent system, but they may not be as action-guiding for systems in our near to medium term future.

For an example of the type of problem that I am worried about, but in a different domain, consider Georgism, the idea of deriving all government revenues from a land value tax. From a recent blogpost by David Friedman: “since it is taxing something in perfectly inelastic supply, taxing it does not lead to any inefficient economic decisions. The site value does not depend on any decisions made by its owner, so a tax on it does not distort his decisions, unlike a tax on income or produced goods.”

Now, this reasoning appears to be sound. Many people have been persuaded by it. However, because the concepts are imperfect, there can still be flaws. One possible flaw might be that the land value would have to be measured, and that inefficiency might come from there. Another possible flaw was recently pointed out by David Friedman in the blogpost linked above, which I understand as follows: the land value tax rewards counterfactual improvement, and this leads to predictable inefficiencies because you want to be rewarding Shapley value instead, which is much more difficult to estimate.

I think that these issues are fairly severe when attempting to make predictions for events further in the horizon, e.g., ten, thirty years. The concepts shift like sand under your feet.

Uneasiness about selection effects at the level of arguments

I am uneasy about what I see as selection effects at the level of arguments. I think that there is a small but intelligent community of people who have spent significant time producing some convincing arguments about AGI, but no community which has spent the same amount of effort looking for arguments against.

Here is a neat blogpost by Phil Trammel on this topic.

Here are some excerpts from a casual discussion among Samotsvety Forecasting team members:

The selection effect story seems pretty broadly applicable to me. I’d guess most Christian apologists, Libertarians, Marxists, etc. etc. etc. have a genuine sense of dialectical superiority: “All of these common objections are rebutted in our FAQ, yet our opponents aren’t even aware of these devastating objections to their position”, etc. etc.

You could throw in bias in evaluation too, but straightforward selection would give this impression even to the fair-minded who happen to end up in this corner of idea space. There are many more ‘full time’ (e.g.) Christian apologists than anti-apologists, so the balance of argumentative resources (and so apparent balance of reason) will often look slanted.

This doesn’t mean the view in question is wrong: back in my misspent youth there were similar resources re, arguing for evolution vs. creationists/ID (https://www.talkorigins.org/). But it does strongly undercut “but actually looking at the merits clearly favours my team” alone as this isn’t truth tracking (more relevant would be ‘cognitive epidemiology’ steers: more informed people tend to gravitate to one side or another, proponents/opponents appear more epistemically able, etc.)

An example for me is Christian theology. In particular, consider Aquinas' five proofs of good (summarized in Wikipedia), or the various ontological arguments. Back in the day, in took me a bit to a) understand what exactly they are saying, and b) understand why they don’t go through. The five ways in particular were written to reassure Dominican priests who might be doubting, and in their time they did work for that purpose, because the topic is complex and hard to grasp.

You should be worried about the ‘Christian apologist’ (or philosophy of religion, etc.) selection effect when those likely to discuss the view are selected for sympathy for it. Concretely, if on acquaintance with the case for AI risk your reflex is ‘that’s BS, there’s no way this is more than 1/million’, you probably aren’t going to spend lots of time being a dissident in this ‘field’ versus going off to do something else.

This gets more worrying the more generally epistemically virtuous folks are ‘bouncing off’: e.g. neuroscientists who think relevant capabilities are beyond the ken of ‘just add moar layers’, ML Engineers who think progress in the field is more plodding than extraordinary, policy folks who think it will be basically safe by default etc. The point is this distorts the apparent balance of reason - maybe this is like Marxism, or NGDP targetting, or Georgism, or general semantics, perhaps many of which we will recognise were off on the wrong track.

(Or, if you prefer being strictly object-level, it means the strongest case for scepticism is unlikely to be promulgated. If you could pin folks bouncing off down to explain their scepticism, their arguments probably won’t be that strong/have good rebuttals from the AI risk crowd. But if you could force them to spend years working on their arguments, maybe their case would be much more competitive with proponent SOTA).

It is general in the sense there is a spectrum from (e.g.) evolutionary biology to (e.g.) Timecube theory, but AI risk is somewhere in the range where it is a significant consideration.

It obviously isn’t an infallible one: it would apply to early stage contrarian scientific theories and doesn’t track whether or not they are ultimately vindicated. You rightly anticipated the base-rate-y reply I would make.

Garfinkel and Shah still think AI is a very big deal, and identifying them at the sceptical end indicates how far afield from ‘elite common sense’ (or similar) AI risk discussion is. Likewise I doubt that there are some incentives to by a dissident from this consensus means there isn’t a general trend in selection for those more intuitively predisposed to AI concern.

There are some possible counterpoints to this, and other Samotsvety Forecasting team members made those, and that’s fine. But my individual impression is that the selection effects argument packs a whole lot of punch behind it.

One particular dynamic that I’ve seen some gung-ho AI risk people mention is that (paraphrasing): “New people each have their own unique snowflake reasons for rejecting their particular theory of how AI doom will develop. So I can convince each particular person, but only by talking to them individually about their objections.”

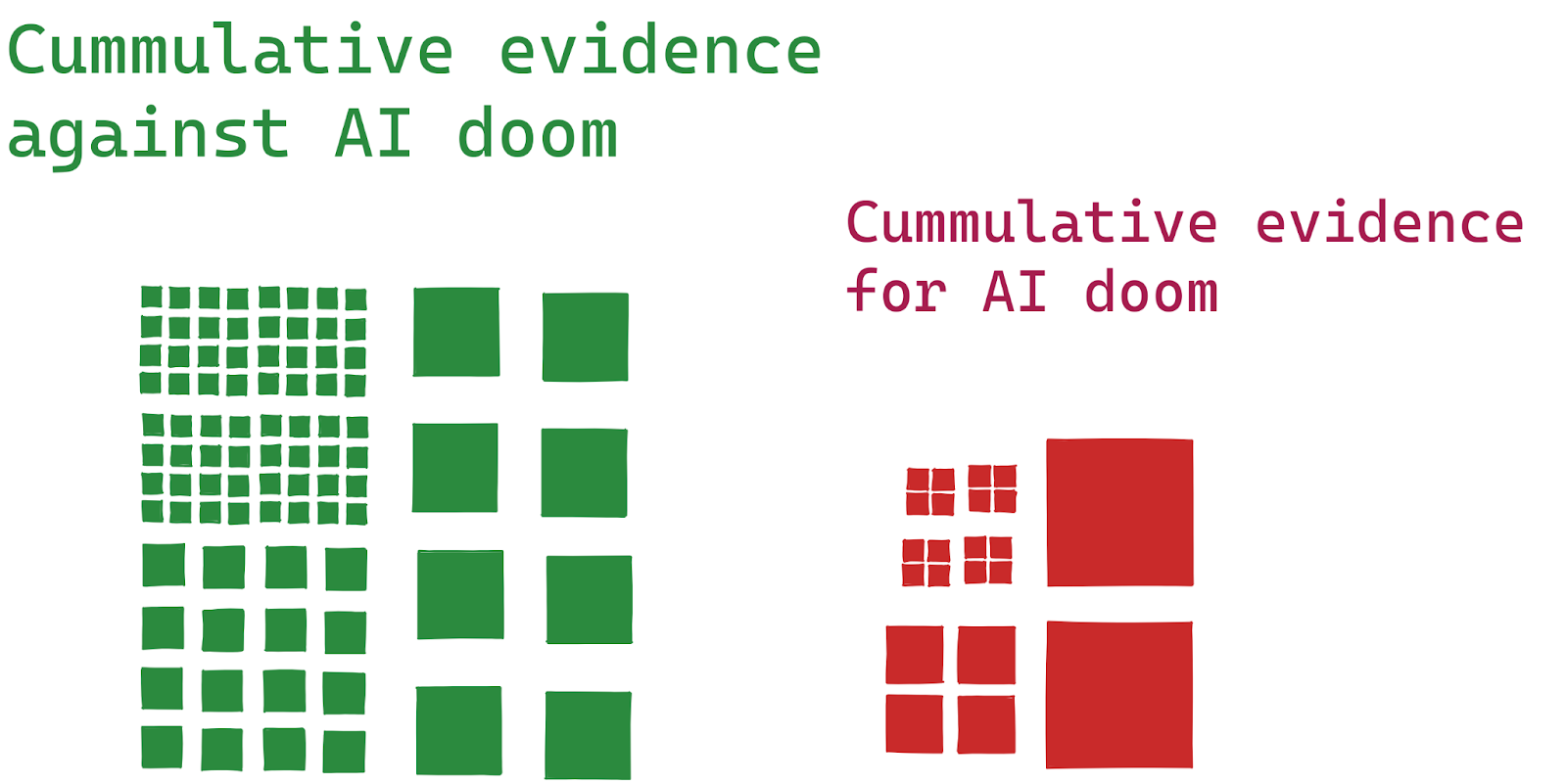

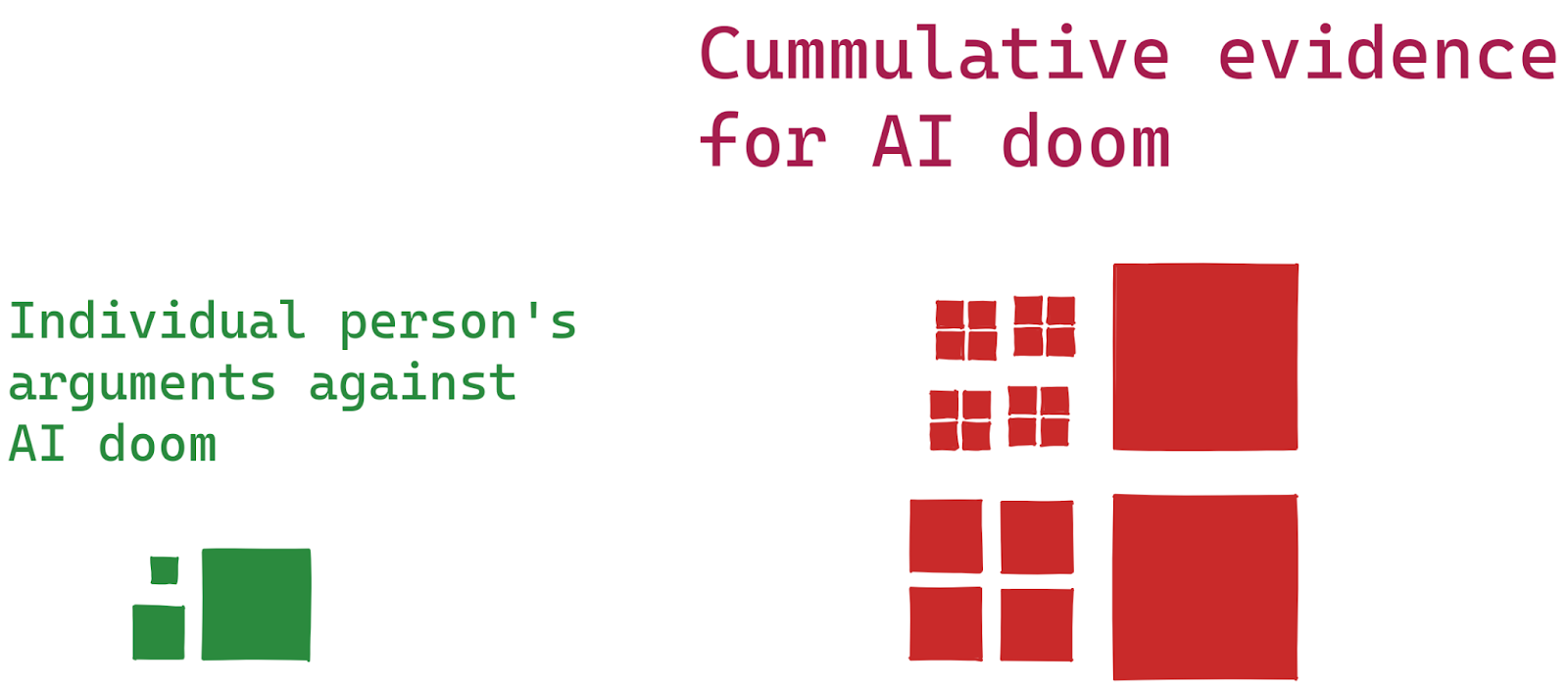

So, in illustration, the overall balance could look something like:

Whereas the individual matchup could look something like:

And so you would expect the natural belief dynamics stemming from that type of matchup.

What you would want to do is to have all the evidence for and against, and then weigh it.

I also think that there are selection effects around which evidence surfaces on each side, rather than only around which arguments people start out with.

It is interesting that when people move to the Bay area, this is often very “helpful” for them in terms of updating towards higher AI risk. I think that this is a sign that a bunch of social fuckery is going on. In particular, I think it might be the case that Bay area movement leaders identify arguments for shorter timelines and higher probability of x-risk with “the rational”, which produces strong social incentives to be persuaded and to come up with arguments in one direction.

More specifically, I think that “if I isolate people from their normal context, they are more likely to agree with my idiosyncratic beliefs” is a mechanisms that works for many types of beliefs, not just true ones. And more generally, I think that “AI doom is near” and associated beliefs are a memeplex, and I am inclined to discount their specifics.

Miscellanea

Difference between in-argument reasoning and all-things-considered reasoning

I’d also tend to differentiate between the probability that an argument or a model gives, and the all-things considered probability. For example, I might look at Ajeya’s timeline, and I might generate a probability by inputting my curves in its model. But then I would probably add additional uncertainty on top of that model.

My weak impression is that some of the most gung-ho people do not do this.

Methodological uncertainty

It’s unclear whether we can get good accuracy predicting dynamics that may happen across decades. I might be inclined to discount further based on that. One particular uncertainty that I worry about is that we can get “AI will be a big deal and be dangerous”, but that danger taking a different shape than what we expected.

For this reason, I am more sympathetic to tools other than forecasting for long-term decision-making, e.g., as outlined here.

Uncertainty about unknown unknowns

I think that unknown unknowns mostly delay AGI. E.g., covid, nuclear war, and many other things could lead to supply chain disruptions. There are unknown unknowns in the other direction, but the higher one’s probability goes, the more unknown unknowns should shift one towards 50%.

Updating on virtue

I think that updating on virtue is a legitimate move. By this I mean to notice how morally or epistemically virtuous someone is, to update based on that about whether their arguments are made in good faith or from a desire to control, and to assign them more or less weight accordingly.

I think that a bunch of people around the CFAR cluster that I was exposed to weren’t particularly virtuous and willing to go to great lengths to convince people that AI is important. In particular, I think that isolating people from the normal flow of their lives for extended periods has an unreasonable effectiveness at making them more pliable and receptive to new and weird ideas, whether they are right or wrong. I am a bit freaked out about the extent to which ESPR, a rationality camp for kids in which I participated, did that.

(Brief aside: An ESPR instructor points out that ESPR separated itself from CFAR after 2019, and has been trying to mitigate these factors. I do think that the difference is important, but this post isn’t about ESPR in particular but about AI doom skepticism and so will not be taking particular care here.)

Here is a comment from a CFAR cofounder, which has since left the organization, taken from this Facebook comment thread (paragraph divisions added by me):

Question by bystander: Around 3 minutes, you mention that looking back, you don’t think CFAR’s real drive was _actually_ making people think better. Would be curious to hear you elaborate on what you think the real drive was.

Answer: I’m not going to go into it a ton here. It’ll take a bit for me to articulate it in a way that really lands as true to me. But a clear-to-me piece is, CFAR always fetishized the end of the world. It had more to do with injecting people with that narrative and propping itself up as important.

We did a lot of moral worrying about what “better thinking” even means and whether we’re helping our participants do that, and we tried to fulfill our moral duty by collecting information that was kind of related to that, but that information and worrying could never meaningfully touch questions like “Are these workshops worth doing at all?” We would ASK those questions periodically, but they had zero impact on CFAR’s overall strategy.

The actual drive in the background was a lot more like “Keep running workshops that wow people” with an additional (usually consciously (!) hidden) thread about luring people into being scared about AI risk in a very particular way and possibly recruiting them to MIRI-type projects.

Even from the very beginning CFAR simply COULD NOT be honest about what it was doing or bring anything like a collaborative tone to its participants. We would infantilize them by deciding what they needed to hear and practice basically without talking to them about it or knowing hardly anything about their lives or inner struggles, and we’d organize the workshop and lectures to suppress their inclination to notice this and object.

That has nothing to do with grounding people in their inner knowing; it’s exactly the opposite. But it’s a great tool for feeling important and getting validation and coercing manipulable people into donating time and money to a Worthy Cause™ we’d specified ahead of time. Because we’re the rational ones, right? 😛

The switch Anna pushed back in 2016 to CFAR being explicitly about xrisk was in fact a shift to more honesty; it just abysmally failed the is/ought distinction in my opinion. And, CFAR still couldn’t quite make the leap to full honest transparency even then. (“Rationality for its own sake for the sake of existential risk” is doublespeak gibberish. Philosophical summersaults won’t save the fact that the energy behind a statement like that is more about controlling others' impressions than it is about being goddamned honest about what the desire and intention really is.)

The dynamics at ESPR, a rationality camp I was involved with, were at times a bit more dysfunctional than that, particulary before 2019. For that reason, I am inclined to update downwards. I think that this is a personal update, and I don’t necessarily expect it to generalize.

I think that some of the same considerations that I have about ESPR might also hold for those who have interacted with people seeking to persuade, e.g., mainline CFAR workshops, 80,000 hours career advising calls, ATLAS, or similar. But to be clear I haven’t interacted much with those other groups myself and my sense is that CFAR—which organize iterations of ESPR up to 2019—went off the guardrails but that these other organizations haven’t.

Industry vs AI safety community

It’s unclear to me what the views of industry people are. In particular, the question seems a bit confused. I want to get at the independent impression that people get from working with state-of-the-art AI models. But industry people may already be influenced by AI safety community concerns, so it’s unclear how to isolate the independent impression. Doesn’t seem undoable, though.

Suggested decompositions

The above reasons for skepticism lead me to suggest the following decompositions for my forecasting group, Samotsvety, to use when forecasting AGI and its risks:

Very broad decomposition

I:

- Will AGI be a big deal?

- Conditional on it being “a big deal”, will it lead to problems?

- Will those problems be existential?

II:

- AI capabilities will continue advancing

- The advancement of AI capabilities will lead to social problems

- … and eventually to a great catastrophe

- … and eventually to human extinction

Are we right about this stuff decomposition

- We are right about this AGI stuff

- This AGI stuff implies that AGI will be dangerous

- … and it will lead to human extinction

Inside the model/outside the model decomposition

I:

- Model/Decomposition X gives a probability

- Are the concepts in the decomposition robust enough to support chains of inference?

- What is the probability of existential risk if they aren’t?

I:

- Model/Decomposition X gives a probability

- Is model X roughly correct?

- Are the concepts in the decomposition robust enough to support chains of inference?

- Will the implicit assumptions that it is making pan out?

- What is the probability of existential risk if model X is not correct?

Implications of skepticism

I view the above as moving me away from certainty that we will get AGI in the short term. For instance, I think that having 70 or 80%+ probabilities on AI catastrophe within our lifetimes is probably just incorrect, insofar as a probability can be incorrect.

Anecdotally, I recently met someone at an EA social event that a) was uncalibrated, e.g., on Open Philanthropy’s calibration tool, but b) assigned 96% to AGI doom by 2070. Pretty wild stuff.

Ultimately, I’m personally somewhere around 40% for “By 2070, will it become possible and financially feasible to build advanced-power-seeking AI systems?”, and somewhere around 10% for doom. I don’t think that the difference matters all that much for practical purposes, but:

- I am marginally more concerned about unknown unknowns and other non-AI risks

- I would view interventions that increase civilizational robustness (e.g., bunkers) more favourably, because these are a bit more robust to unknown risks and could protect against a wider range or risks

- I don’t view AGI soon as particularly likely

- I view a stance which “aims to safeguard humanity through the 21st century” as more appealing than “Oh fuck AGI risk”

Conclusion

I’ve tried to outline some factors about why I feel uneasy with high existential risk estimates. I view the most important points as:

- Distrust of reasoning chains using fuzzy concepts

- Distrust of selection effects at the level of arguments

- Distrust of community dynamics

It’s not clear to me whether I have bound myself into a situation in which I can’t update from other people’s object-level arguments. I might well have, and it would lead to me playing in a perhaps-unnecessary hard mode.

If so, I could still update from e.g.:

- Trying to make predictions, and seeing which generators are more predictive of AI progress

- Investigations that I do myself, that lead me to acquire independent impressions, like playing with state-of-the-art models

- Deferring to people that I trust independently, e.g., Gwern

Lastly, I would loathe it if the same selection effects applied to this document: If I spent a few days putting this document together, it seems easy for the AI safety community to easily put a few cumulative weeks into arguing against this document, just by virtue of being a community.

This is all.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Samotsvety forecasters that have discussed this topic with me, and to Ozzie Gooen for comments and review. The above post doesn’t necessarily represent the views of other people at the Quantified Uncertainty Research Institute, which nonetheless supports my research.