Just-in-time Bayesianism

I propose a simple variant of subjective Bayesianism that I think captures some important aspects of how humans1 reason in practice given that Bayesian inference is normally too computationally expensive. I apply it to the problem of trapped priors, to discounting small probabilities, and mention how it relates to other theories in the philosophy of science.

A motivating problem in subjective Bayesianism

Bayesianism as an epistemology has elegance and parsimony, stemming from its inevitability as formalized by Cox’s theorem. For this reason, it has a certain magnetism as an epistemology.

However, consider the following example: a subjective Bayesian which has only two hypothesis about a coin:

\[ \begin{cases} \text{it has bias } 2/3\text{ tails }1/3 \text{ heads }\\ \text{it has bias } 1/3\text{ tails }2/3 \text{ heads } \end{cases} \]

Now, as that subjective Bayesian observes a sequence of coin tosses, he might end up very confused. For instance, if he only observes tails, he will end up assigning almost all of his probability to the first hypothesis. Or if he observes 50% tails and 50% heads, he will end up assigning equal probability to both hypotheses. But in neither case are his hypotheses a good representation of reality.

Now, this could be fixed by adding more hypotheses, for instance some probability density to each possible bias. This would work for the example of a coin toss, but might not work for more complex real-life examples: representing many hypothesis about the war in Ukraine or about technological progress in their fullness would be too much for humans.2

So on the one hand, if our set of hypothesis is too narrow, we risk not incorporating a hypothesis that reflects the real world. But on the other hand, if we try to incorporate too many hypothesis, our mind explodes because it is too tiny. Whatever shall we do?

Just-in-time Bayesianism by analogy to just-in-time compilation

Just-in-time compilation refers to a method of executing programs such that their instructions are translated to machine code not at the beginning, but rather as the program is executed.

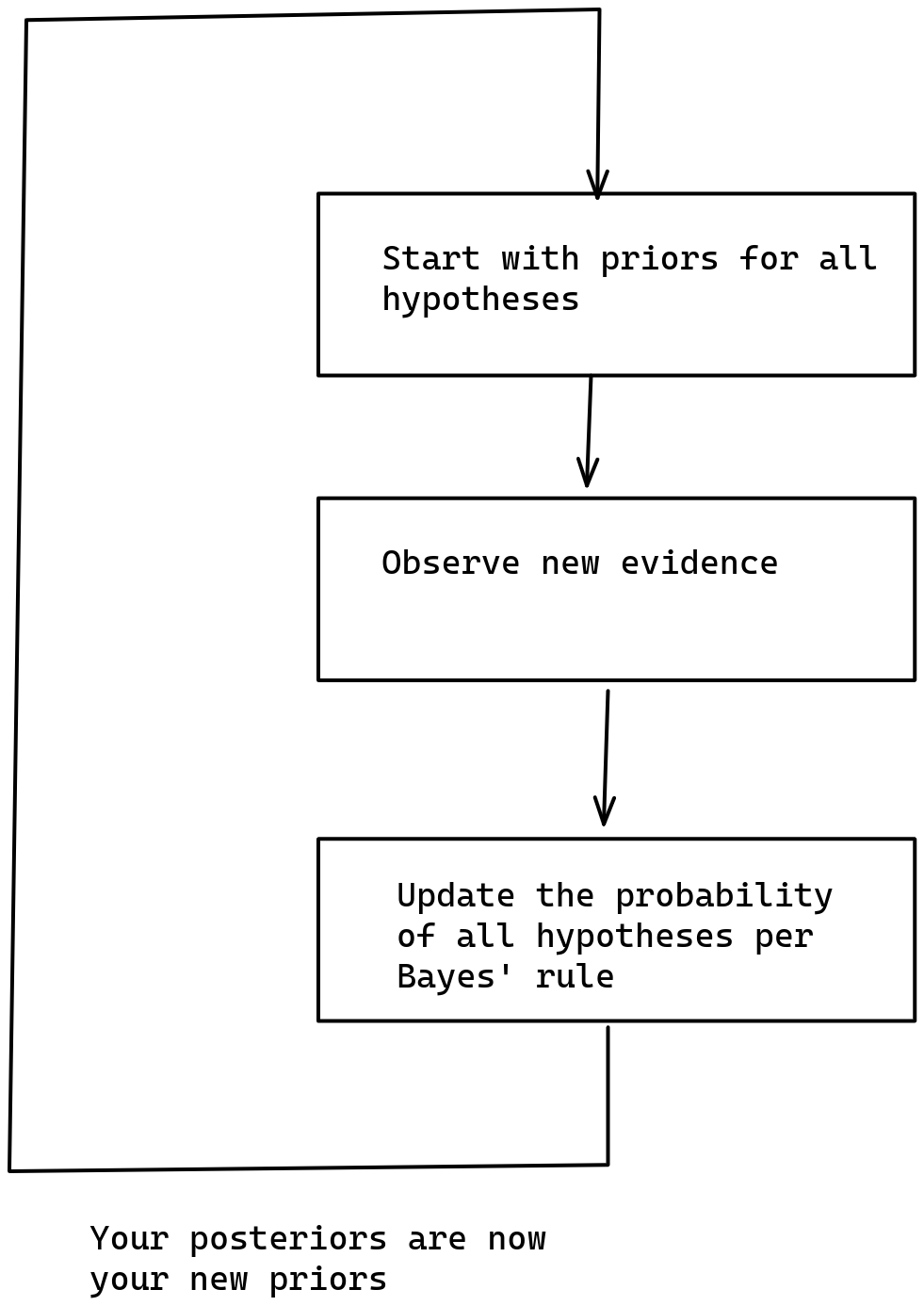

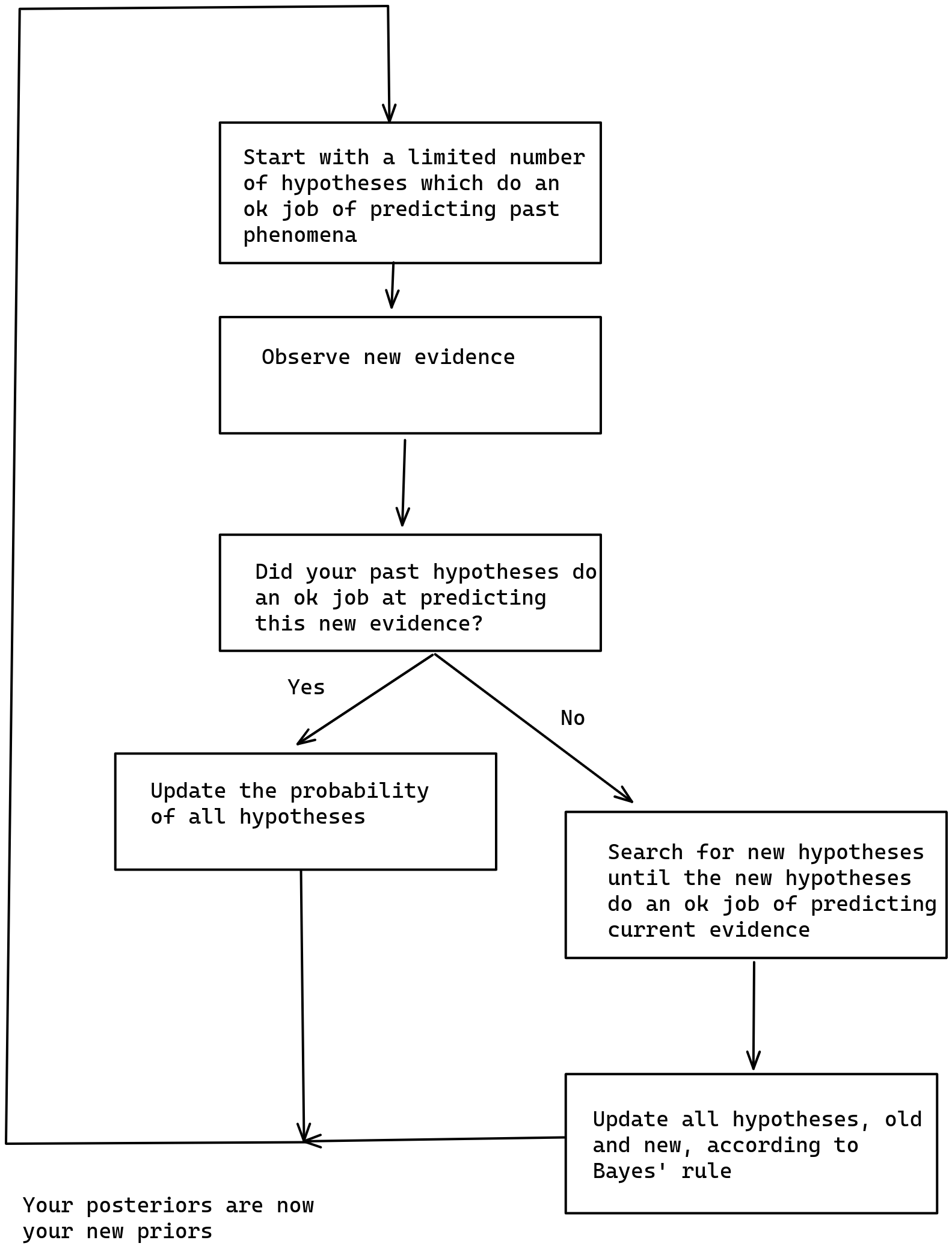

By analogy, I define just-in-time Bayesianism as a variant of subjective Bayesian where inference is initially performed over a limited number of hypothesis, but if and when these hypothesis fail to be sufficiently predictive of the world, more are searched for and past Bayesian inference is recomputed. This would look as follows:

I intuit that this method could be used to run a version of Solomonoff induction that converges to the correct hypothesis that describes a computable phenomenon in a finite (but still enormous) amount of time. More generally, I intuit that just-in-time Bayesianism will have some nice convergence guarantees.

As this relates to…

ignoring small probabilities

Kosonen 2022 explores a setup in which an agent ignores small probabilities of vast value, in the context of trying to deal with the “fanaticism” of various ethical theories.

Here is my perspective on this dilemma:

- On the one hand, neglecting small probabilities has the benefit of making expected calculations computationally tractable: if we didn’t ignore at least some possibilities, we would never finish these calculations.

- But on the other hand, the various available methods for ignoring small probabilities are not robust. For example, they are not going to be robust to situations in which these probabilities shift (see p. 181, “The Independence Money Pump”, Kosonen 2022).

- For example, one could have been very sure that the Sun orbits the Earth—which could have some theological and moral implications—and thus initially assign a ver small probability to the reverse. But if one ignores very small probabilities ex-ante, one might not able to update in the face of new evidence.

- Similarly, one could have assigned very small probability to a world war. But if one initialy discarded this probability completely, one would not be able to update in the face of new evidence as war approaches.

Just-in-time Bayesianism might solve this problem by indeed ignoring small probabilities at the beginning, but expanding the search for hypotheses if current hypotheses aren’t very predictive of the world we observe. In particular, if the chance of a possibility rises continuously before it happens, just-in-time Bayesianism might have some time to deal with new unexpected possibilities.

…the problem of trapped priors

In Trapped Priors As A Basic Problem Of Rationality, Scott Alexander considers the case of a man who was previously unafraid of dogs, and then had a scary experience related to a dog—for our purposes imagine that they were bitten by a dog.

Just-in-time Bayesianism would explain this as follows.

- At the beginning, the man had just one hypothesis, which is “dogs are fine”

- The man is bitten by a dog. Society claims that this was a freak accident, but this doesn’t explain the man’s experiences. So the man starts a search for new hypotheses

- After the search, the new hypotheses and their probabilities might be something like:

\[ \begin{cases} \text{1. Dogs are fine, this was just a freak accident }\\ \text{2. Society is lying: Dogs are not fine, but rather they bite}\\ \text{with a frequency of } \frac{2}{n+2} \text{,where n is the number of total}\\ \text{encounters the man has had} \end{cases} \]

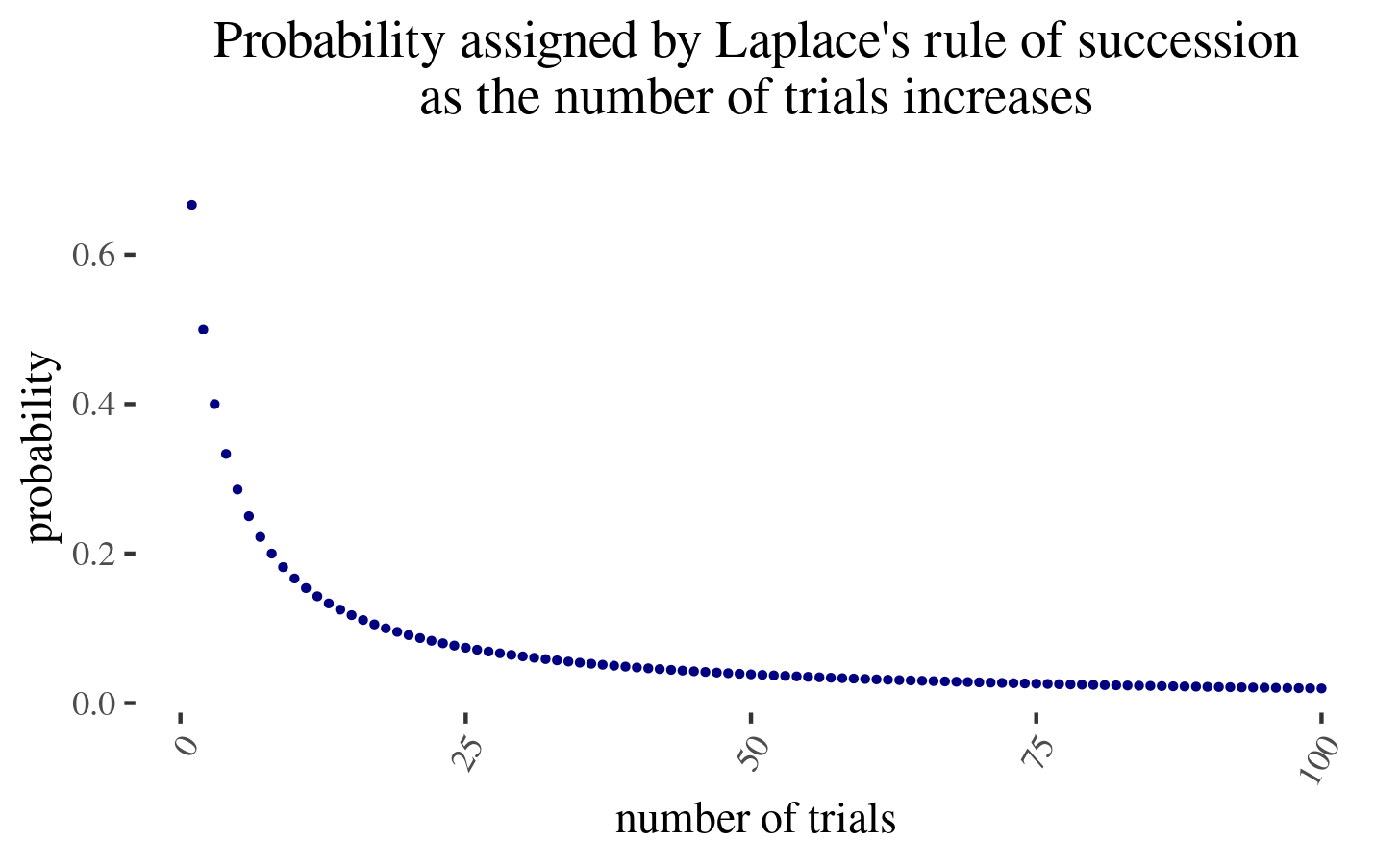

The second estimate is the estimate produced by Laplace’s law—an instance of Bayesian reasoning given an ignorance prior—given one “success” (a dog biting a human) and \(n\) “failures” (a dog not biting a human).

Now, because the first hypothesis assigns very low probability to what the man has experienced, a whole bunch of the probability goes to the second hypothesis. Note that the prior degree of credence to assign to this second hypothesis isn’t governed by Bayes' law, and so one can’t do a straightforward Bayesian update.

But now, with more and more encounters, the probability assigned by the second hypothesis, will be as \(\frac{2}{n+2}\), where \(n\) is the number of times the man interacts with a dog. But this goes down very slowly:

In particular, you need to double the amount of interactions with a dog and then condition on them going positively (no bites) for \(p(n) =\frac{2}{n+2}\) to halve. But note that this in expectation approximately produces another two dog bites3! Hence the optimal move might be to avoid encountering new evidence (because the chance of another dog bite is now too large), hence the trapped priors.

…philosophy of science

The strong programme in the sociology of science aims to explain science only with reference to the sociological conditionst that bring it about. There are also various accounts of science which aim to faithfully describe how science is actually practiced.

Well, I’m more attracted to trying to explain the workings of science with reference to the ideal mechanism from which they fall short. And I think that just-in-time Bayesianism parsimoniously explains some aspects with reference to:

- Bayesianism as the optimal/rational procedure for assigning degrees of belief to statements.

- necessary patches which result from the lack of infinite computational power.

As a result, just-in-time Bayesianism not only does well in the domains in which normal Bayesianism does well: - It smoothly processes the distinction between background knowledge and new revelatory evidence - It grasps that both confirmatory and falsificatory evidence are important—which inductionism/confirmationism and naïve forms of falsificationism both fail at - It parsimoniously dissolves the problem of induction: one never reaches certainty, and instead accumulates Bayesian evidence.

But it is also able to shed some light in some phenomena where alternative theories of science have traditionally fared better:

- It interprets the difference between scientific revolutions (where the paradigm changes) and normal science (where the implications of the paradigm are fleshd out) as a result of finite computational power

- It does a bit better at explaining the problem of priors, where the priors are just the hypothesis that humanity has had enough computing power to generate.

Though it is still not perfect

- the “problem of priors” is still not really dissolved to a nice degree of satisfaction.

- the step of acquiring more hypotheses is not really explained, and it is also a feature of other philosophies of science, so it’s unclear that this is that much of a win for just-in-time Bayesianism.

So anyways, in philosophy of science the main advantages that just-in-time Bayesianism has is being able to keep some of the more compelling features of Bayesianism, while at the same time also being able to explain some features that other philosophy of science theories have.

Some other related theories and alternatives.

- Non-Bayesian epistemology: e.g., falsificationism, positivism, etc.

- Infra-Bayesianism, a theory of Bayesianism which, amongst other things, is robust to adversaries filtering evidence

- Logical induction, which also seems uncomputable on account of considering all hypotheses, but which refines itself in finite time

- Predictive processing, in which an agent changes the world so that it conforms to its internal model.

- etc.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I sketched a simple variation of subjective Bayesianism that is able to deal with limited computing power. I find that it sheds some clarity in various fields, and considered cases in the philosophy of science, discounting small probabilities in moral philosophy, and the applied rationality community.

- I think that the model has more explanatory power when applied to groups of humans that can collectively reason.↩

- In the limit, we would arrive at Solomonoff induction, a model of perfect inductive inference that assigns a probability to all computable hypothesis. Here is an explanation of Solomonoff induction4.↩

- \(E[\text{new bites}] = n \cdot p(bite) = n \cdot \frac{2}{n+2} \approx 2\). Note that this is ex-ante, as one is deciding whether to gather more evidence.↩

- The author appears to be the cofounder of DeepMind.↩