Straightforwardly eliciting probabilities from GPT-3

I explain two straightforward strategies for eliciting probabilities from language models, and in particular for GPT-3, provide code, and give my thoughts on what I would do if I were being more hardcore about this.

Straightforward strategies

Look at the probability of yes/no completion

Given a binary question, like “At the end of 2023, will Vladimir Putin be President of Russia?” you can create something like the following text for the model to complete:

At the end of 2023, will Vladimir Putin be President of Russia? [Yes/No]

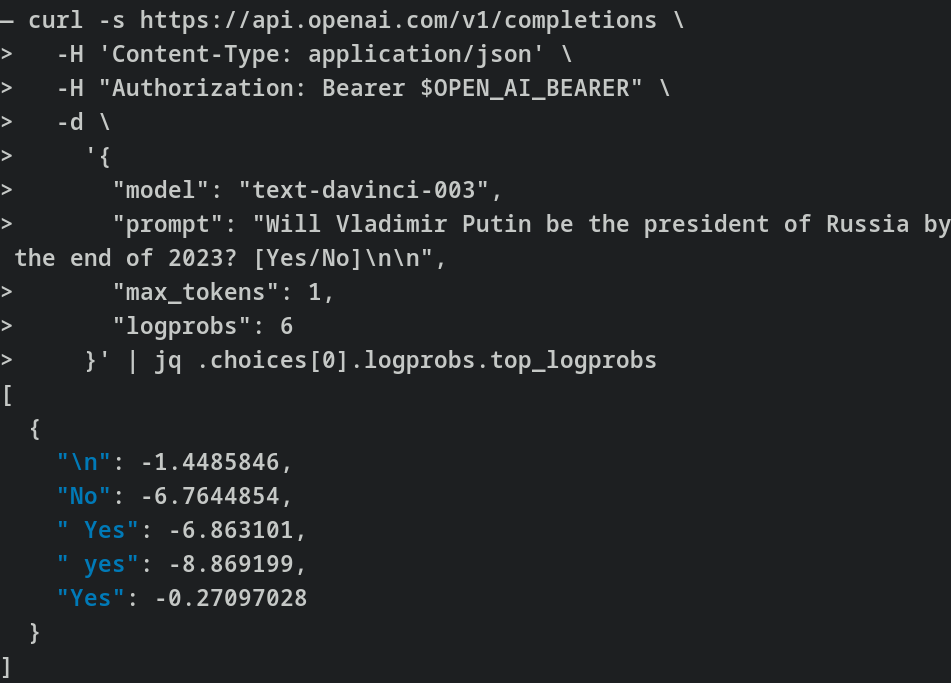

Then we can compare the relative probabilities of completion to the “Yes,” “yes,” “No” and “no” tokens. This requires a bit of care. Note that we are not making the same query 100 times and looking at the frequencies, but rather asking for the probabilities directly:

You can see a version of this strategy implemented here.

A related strategy might be to look at what probabilities the model assigns to a pair of sentences with opposite meanings:

- “Putin will be the president of Russia in 2023”

- “Putin will not be the president of Russia in 2023.”

For example, GPT-3 could assign a probability of 9 * 10^-N to the first sentence and 10^-N to the second sentence. We could then interpret that as a 90% probability that Putin will be president of Russia by the end of 2023.

But that method has two problems:

- The negatively worded sentence has one word more, and so it might systematically have a lower probability

- GPT-3’s API doesn’t appear to provide a way of calculating the likelihood of a whole sentence.

Have the model output the probability verbally

You can directly ask the model for a probability, as follows:

Will Putin be the president of Russia in 2023? Probability in %:

Now, the problem with this approach is that, untweaked, it does poorly.

Instead, I’ve tried to use templates. For example, here is a template for producing reasoning in base rates:

Many good forecasts are made in two steps.

- Look at the base rate or historical frequency to arrive at a baseline probability.

- Take into account other considerations and update the baseline slightly.

For example, we can answer the question “will there be a schism in the Catholic Church in 2023?” as follows:

- There have been around 40 schisms in the 2000 years since the Catholic Church was founded. This is a base rate of 40 schisms / 2000 years = 2% chance of a schism / year. If we only look at the last 100 years, there have been 4 schisms, which is a base rate of 4 schisms / 100 years = 4% chance of a schism / year. In between is 3%, so we will take that as our baseline.

- The Catholic Church in Germany is currently in tension and arguing with Rome. This increases the probability a bit, to 5%.

Therefore, our final probability for “will there be a schism in the Catholic Church in 2023?” is: 5%

For another example, we can answer the question “${question}” as follows:

That approach does somewhat better. The problem is that sometimes the base rate approach isn’t quite relevant, because sometimes we have neither a historical record—e.g,. global nuclear war. And sometimes we can’t straightforwardly rely on the lack of a historical track record: VR headsets haven’t really been adopted in the mainstream, but their price has been falling and their quality rising, so making a forecast solely looking at the historical lack of adoption might lead one astray.

You can see some code which implements this strategy here.

More elaborate strategies

Various templates, and choosing the template depending on the type of question

The base rate template is only one of many possible options. We could also look at:

- Laplace rule of succession template: Since X was first possible, how often has it happened?

- “Mainstream plausibility” template: We could prompt a model to simulate how plausible a well-informed member of the public thinks that an event is, and then convert that degree of plausibility into a probability.

- Step-by-step model: What steps need to happen for something to happen, and how likely is each step?

- etc.

The point is that there are different strategies that a forecaster might employ, and we could try to write templates for them. We could also briefly describe them to GPT and ask it to choose on the fly which one would be more relevant to the question at hand.

GPT consulting GPT

More elaborate versions of using “templates” are possible. GPT could decompose a problem into subtasks, delegate these to further instances of GPT, and then synthesize and continue working with the task results. Some of this work has been done by Paul Christiano and others under the headline of “HCH” (Humans consulting HCH) or “amplification.”

However, it appears to me that GPT isn’t quite ready for this kind of thing, because the quality of its reasoning isn’t really high enough to play a game of telephone with itself. Though it’s possible that a more skilled prompter could get better results. Building tooling for GPT-consulting-GPT seems could get messy, although the research lab Ought has been doing some work in this area.

Query and interact with the internet.

Querying the internet seems like an easy win in order to increase a model’s knowledge. In particular, it might not be that difficult to query and summarize up-to-date Wikipedia pages, or Google News articles.

Fine-tune the model on good worked examples of forecasting reasoning

- Collect 100 to 1k examples of worked forecasting questions from good forecasters.

- Fine-tune a model on those worked forecasting rationales.

- Elicit similar reasoning from the model.

Parting thoughts

You can see the first two strategies applied to SlateStarCodex in this Google document.

Overall, the probabilities outputted by GPT appear to be quite mediocre as of 2023-02-06, and so I abandoned further tweaks.

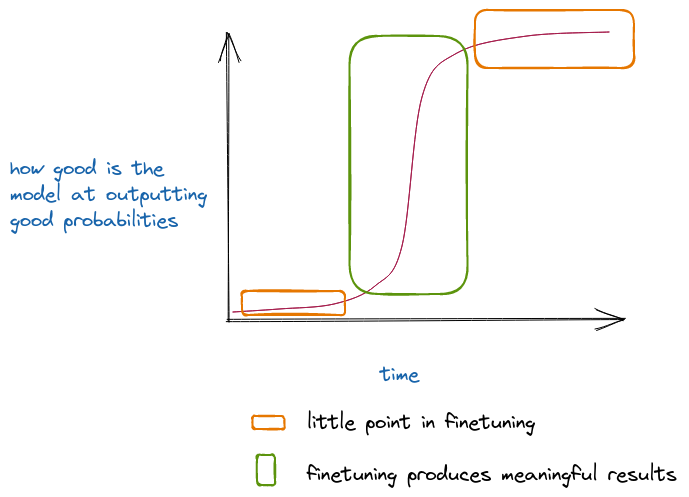

In the above image, I think that we are in the first orange region, where the returns to fine-tuning and tweaking just aren’t that exciting. Though it is also possible that having tweaks and tricks ready might help us identify that the curve is turning steeper a bit earlier.

Acknowledgements

This is a project of the Quantified Uncertainty Research Institute. Thanks to Ozzie Gooen and Adam Papineau for comments and suggestions.