Goodhart’s law and aligning politics with human flourishing

Note: Written for someone I’ve been having political discussions with. For similarly introductory content, see A quick note on the value of donations.

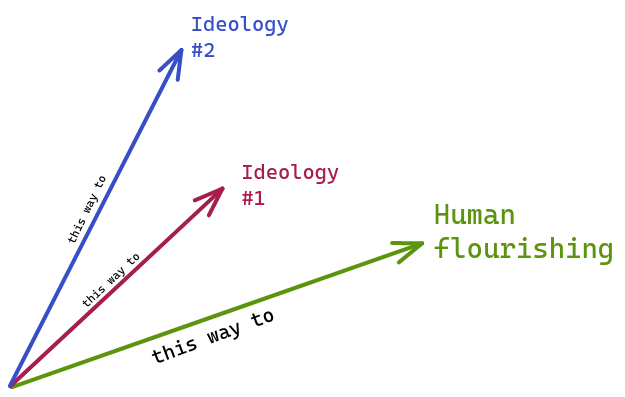

The world’s major ideologies, like neoliberalism and progressivism, are stuck in a stalemate. They’re great at pointing out each other’s flaws, but neither side can make a compelling case for itself the other can’t poke holes into. To understand why, I want to look to Goodhart’s law and presocratic Greek philosophy for insights. Ultimately, though, I think we need better political tools to better align governments and institutions with human flourishing.

The situation

Goodhart’s law cautions against chasing a metric. When you do, you will end up achieving high scores in a way which undermines the metric’s original purpose. For example, a few years ago the Spanish government aimed to reduce deaths from traffic accidents—a worthy goal. But instead of actually saving lives, they simply changed the definition of “traffic accident deaths” to exclude people who died in the hospital days after the accident.

Progressives see this happening with unregulated capitalism. Without regulation, corporations will prioritize profits, even if it means sacrificing human well-being. For example, companies may create addictive games or social media platforms that monopolize our attention. In more extreme cases, they may exploit workers in ways that are outright abusive, such as the Sumangali form of child labor. This is why we need labor protection laws and state intervention—to prevent such exploitation. The key point is that, without regulation, capitalism will inevitably prioritize profit over people.

Neoliberals, on the other hand, rightly point out that relying on the state has its own set of problems. Government inefficiency compared to the private sector, pork-barrel spending, myopic policies resulting from short election cycles, or corruption of the political process through revolving doors and ultimately regulatory capture can all have harmful effects. Neoliberals argue that market forces can be a powerful tool for generating prosperity, and that these issues should not be overlooked.1

So each side is skilled at articulating its opponent’s weakeness, but is not as able to put forward an impregnable case for its own position. This stalemate is reminiscent of early presocratic philosophy. Thale and Anaximenes, for example, both put forth theories about the elemental composition of the universe—one claiming everything was made of water, the other asserting everything was made of air. Like politics today, each could see that the other was wrong, but they couldn’t convince the other side.

The root of the problem is that both sides of this debate are in the wrong. Each side contains an inherent rhetorical contradiction: they advocate for an imperfect mechanism that doesn’t always prioritize human flourishing, while not realizing the degree to which it will not. This is my diagnosis for the current political stalemate.

Proposed solutions

At the individual level, you could consciously avoid actions that make society shittier, like refusing job opportunities for a tobacco companies, or personally resisting creating irritating advertisements. You could also advocate for stronger social norms that discourage others from engaging in similar behaviors.

At the societal level, the solution is less clear, and I think requires some ideation. Some solutions which I brainstormed were to:

- Rely on political figures who can bridge ideological divides and understand the importance of multiple perspectives.

- Come up with better mechanisms to align governments and human flourishing

- Come up with better mechanisms to align markets and human flourishing

- Periodically re-founding states and institutions to rid them of ideological cruft and realign them with human flourishing

- Have more innovation around forms of government, perhaps within smaller states or with entities such as Próspera

- Read the literature on regulatory economics and related areas.

The Effective Altruism (EA) movement doesn’t have great answers here. It suggests to rigorously rank problems in the world and start working on them in order of importance. But this isn’t a powerful enough answer to run a state. Other ideologies offer different embryonic approaches of how to proceed. The vision sketched in State Capacity Libertarianism presents a libertarianism tweaked to deal with problems requiring large amounts of coordination, but is lacking in detail. My sense is also that some recent feminist/progressive anthropology and social science also has the aim of highlighting or conceiving new types of societies in whose image we would improve our own society.

All in all, the above analysis seems fairly rough. For one, it at time assumes that people share the same goals, and just differ in the mechanisms they think are best to achieve these common goals. Still, perhaps the above is clarifying to some readers.

- To be honest, my personal experience has been that neoliberals are able to acknowledge that capitalism is an imperfect systems, but still defend that it’s a better system than others humanity has tried. Progressives can also be more or less nuancedly anti-market. So the above two paragraphs are just a quick sketch.↩