Unflattering aspects of Effective Altruism

1. I want to better understand in order to better decide

As a counterbalance to the rosier and more philosophical perspective that Effective Altruism (EA) likes to present of itself, I describe some unflattering aspects of EA. These are based on my own experiences with it, and my own disillusionments1.

If people getting into EA2 have a better idea of what they are getting into, and decide to continue, maybe they’ll think twice, interact with EA less naïvely and more strategically, and not become as disillusioned as I have.

But also, the EA machine has been making some weird and mediocre moves, leaving EA as a whole as a not very formidable army3. A leitmotiv from the Spanish epic poem The Song of the Cid is “God, what a good knight would the Cid be, if only he had a good lord to serve under”. As in the story of the Cid then, so in EA now. As a result, I think it makes sense for the rank and file EAs to more often do something different from EA™, from EA-the-meme. To notice that taking EA money carries costs. To reflect on whether the EA machine is better than their outside options. To walk away more often.

2. That the structural organization of the movement is distinct from the philosophy

Effective altruism’s philosophical ideas are seductive: who wants to be less effective? who wants to work on intractable, overgrazed and worthless projects, as opposed to tractable, neglected and impactful problems? But liking the philosophy doesn’t mean you will like the actual movement, or that you should join it. You can have many different kinds of organizational structures corresponding to the same philosophy, and some will be a poor fit for you.

For example, after the 2008 crisis, one could be in favor of reforming the US financial system and holding those responsible for the 2008 crisis accountable, but find Occupy Wall Street deeply disappointing. Historically, there has been huge confusion about this point in EA.4

3. and EA structurally orients itself around one billionaire’s money.

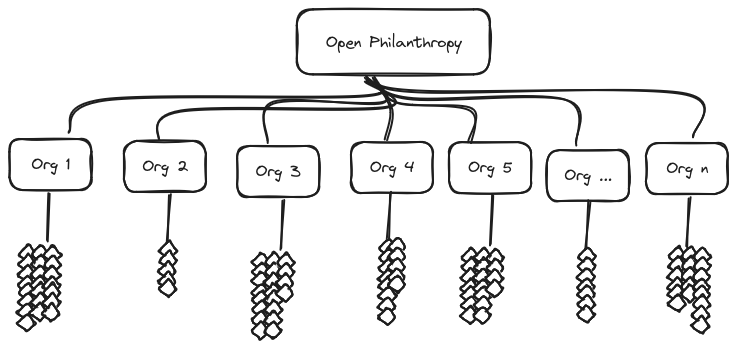

To a first approximation, the structural organization of Effective Altruism is as follows:

- Dustin Moskovitz, a deca-billionaire, is giving his fortune away through his foundation. His foundation, Open Philanthropy, has a large staff subdivided into cause areas.

- Organizations are chasing Open Philanthropy’s funding.

- Rank and file members are seeking to work at organizations with Open Philanthropy funding (“EA organizations”)

There are players who do not fit into this scheme, but I would describe their contribution as marginal. Not as irrelevant, mind you, just as very small in comparison with the Open Philanthropy juggernaut. Still, a few points of nuance:

- Dustin Moskovitz (ca. $10B) isn’t the only billionaire giving money to the cluster of organizations under the EA banner. There is also Jaan Tallinn (ca. $1B), which gives under various “Survival and Flourishing” funds. More may be coming.

- There are a few people “earning to give”, or donating independently of Open Philanthropy. The ones I know of are smaller, with a net worth of ca. ~$10M or so.

- Not 100% organizations or individuals in the EA movement are chasing Open Philanthropy funding.

- Sometimes, Open Philanthropy doesn’t donate to projects directly but e.g., donates to some Effective Altruism Fund or to the Centre for Effective Altruism, which donates to the final project.

- etc.5

Still, the decisions of Open Philanthropy end up being decisive. How decisive? Well, Open Philanthropy directs something like 90% of current funding within the EA movement6. So other funders just don’t have as much capacity in comparison. For example, running a 10 person organization in the EA movement really benefits from having backing from Open Philanthropy, because relying on the other funders adds too much uncertainty and volatility. So I’d say that they end up being pretty decisive.

4. In practice, cost-effectiveness estimates keep EA honest, but only for global health

If we have some reliable way of estimating the value of projects, structural organization doesn’t matter that much. You would propose your project, it would be evaluated, and if it was above some cost-effectiveness bar, it would be funded. That is, to a first approximation, what happens within the global health cause area in EA. You can seek to objectively7 estimate the quality-adjusted life years that an intervention saves. You can have an evaluator like GiveWell. And you can have an organization like Charity Entrepreneurship trying to find interventions that would be evaluated favorably by GiveWell.

The situation with animal welfare is a bit messier. Open Philanthropy might be making some quantified estimates, but I don’t recall them being public. And Animal Charity Evaluators, the would-be GiveWell equivalent, doesn’t do quantified estimates of the value of the charities they rank. Still, in principle you could do estimates of value for animal suffering interventions and avoid the problems I outline below.

With longtermism and global catastrophic risks, you don’t have good methods of estimating the value of different interventions, for example of determining that one AI safety research agenda is better than another, or that one AI governance approach is superior. So in practice, you end up relying on the personal judgment of a crowd of amalgamated8 EA leaders for making funding and prioritization decisions.

Historically, Open Philanthropy has been slow to trust people, either as employees or as grantees. So these amalgamated EA leaders have been overworked, busy, unapproachable9. In practice, people go to great lengths to try to approach and socialize with Open Philanthropy employees, like visiting or moving to the very expensive San Francisco Bay area.

That grant-makers are busy and unavailable makes getting access to them hard, because the group has limited available throughput. But say you increase the throughput. Then, if the game and the habits are still to compete for a limited pool of resources, and if there is still infinite demand for free billionaire money, then charismatic grantees close to EA leaders will still out-compete others. Competing for access is still the wrong game to be playing, though, and I resent this; you don’t want to have a pool of talent competing hard for grant-maker attention, you want to have a pool of talent working hard at making the world a better place10.

The same story told from the bottom up is: an aspiring EA starts with the intention of doing large amounts of good, and will try to do something semi-ambitious. Then he’ll find out that funding constraints are a big part of making shit happen. And when solving that funding bottleneck, he will be in a social context where the natural good move is to try to get access and then seduce a busy, overworked, and therefore unavailable coterie of grantmakers11,12. He’ll burn out.

But that’s the wrong game to be playing because if you look at autochthonous EAs, at the rank and file, many are nerds, nerds who are able to do good work but who will find it hard to jockey for access. Their winning move would be not to play, and to gain real power by building something independently.

5. Outside of global health, the leadership of the EA machinery has even more unappealing aspects

Even beyond the sunflower issues, the central EA machinery, at organizations like the Center for Effective Altruism or Open Philanthropy, has other issues that make it unappealing to me as a source of leadership—of guidance, of evaluation, of moral direction:

First, their priorities are different from mine: Open Philanthropy seems fairly committed to worldview diversification, which I consider a mediocre framework. The Center for Effective Altruism cares much more about the reputation of the “Effective Altruism” brand than I do. In general, I get the impression that they want to “be in control”, and reduce variance from people they don’t deeply trust, while at the same time coming to trust people slowly. In contrast, I would prefer to increase formidability, to employ Auftragstaktik.

As a small but very concrete example of the disconnect between my priorities and those of the EA machine, the EA forum has become a worse place for me over the last couple of years; it seems slower, more pushy, more censorious, more paternalistic. It started as a mean lean machine hosting community discussion, and it is now more of a vehicle for pushing ideas CEA wants you to know about. In the process it grew to cost $2M/year (!?!), employ six to eight people. You can see this thought elaborated further here.

Second, I don’t really understand how feedback loops work in Effective Altruism. If someone thinks that Open Philanthropy is making some mistakes, do they ¿write an EA Forum post and hope to get the attention of someone on inside an inner circle? ¿ambush someone at a party? ¿how do they find the party? ¿how do they get heard? Over the past years I’ve had some disagreements with Open Philanthropy around forecasting strategy, worldview diversification, or the wisdom of committing to donate all of Moskovitz’s money before he dies, and I haven’t felt particularly heard.

Third, I feel that EA leadership uses worries about the dangers of maximization to constrain the rank and file in a hypocritical way. If I want to do something cool and risky on my own, I have to beware of the “unilateralist curse” and “build consensus”. But if Open Philanthropy donates $30M to OpenAI, pulls a not-so-well-understood policy advocacy lever that contributed to the US overshooting inflation in 2021, Moskovitz funds Anthropic13 while Anthropic’s President and the CEO of Open Philanthropy were married, and romantic relationships are common between Open Philanthropy officers and grantees, that is ¿an exercise in good judgment? ¿a good ex-ante bet? ¿assortative mating? ¿presumably none of my business?

Fourth, my impression is that the leadership doesn’t see itself accountable to the community, but to their understanding of the philosophy and to the funding source. E.g., Holden Karnofsky, the erstwhile head honcho of Open Philanthropy, for a long time didn’t answer comments on his posts.

Fifth, Open Philanthropy is large enough that it begins to have “seeing like a state” problems, the problems of bureaucracies. It moves slowly, and seems to have an “unfocused glaze”. E.g., it took two years and an extra $100M to exit the criminal justice cause area. Its forecasting grant-making could have used more small experimentation over large grants to existing organizations. For example, Scott Alexander’s grants seem much more exciting than a $8.5 million to Metaculus, but Open Philanthropy chose the $8.5M to Metaculus and warped the forecasting ecosystem and distribution of talent towards Metaculus-shaped things instead of many small experiments14.

So overall, my impression is that the leadership of EA holds a “leadership without consent”, a leadership without much listening and telegraphing one’s priorities so that the leaders can coordinate better with those they lead, and incorporate their perspectives and feedback. It falls on the wrong side of the socialist calculation debate15, and doesn’t compensate enough. And that makes some sense: Open Philanthropy, the main source of funding, is a bureaucracy spun up to spend a billionaire’s wealth according to his16 broad, delegated desires. It would then be surprising if they were able to also skillfully steer and command a 10k strong community, and listen and address their worries, absorb their perspectives. But also as a result, I don’t feel particularly inclined to take my cues from that machinery.

6. …and EA leadership doesn’t display a blistering, white-hot competence

If the EA leadership was, you know, an Arthurian elite which routinely displayed a blistering white hot competence, then I would be more willing to continue pouring my heart and soul into plans of their design in the absence of feedback loops.

But they aren’t, so I’m not.

7. Therefore it might make sense to walk away more often

I see bright-eyed young EAs wanting to roll deeper into the EA rabbit hole and to get employed by EA organizations. They will learn much at first, but later find themselves at the mercy of a machine that can’t hear them. Bad move to walk into that without forewarning. I see the EA machine luring brilliant minds that might be better off trying to amass a small fortune through capitalistic entrepreneurship and then deploying that fortune subject to many fewer constraints. I see people with ambitious visions with their wings clipped because they are illegible to grantmakers, and I think, what good knights they would be, if they had a good lord to serve under.

Perhaps it makes sense to instead do something subtly different from EA, to ignore the implicit vibes and expectations of the EA machine. To sometimes take their funding, but to do your own thing and preserve your ability to comfortably leave. To not serve a billionaire’s notion of the good within a structure with exceedingly poor feedback loops. To notice that if you could do well inside the EA machine, you might do better outside of it. And sometimes, to simply walk away, to burn the remainder of your youth in the pursuit of making the world a better place, outside of EA.

- You can read a bit more about what I was trying to do here, and some more reflections here.↩

- That is, I think this blog post could plausibly be useful for individual people reading it, not for EA institutionally to address the aspects I discuss. I don’t think there is an EA entity with the inclination to digest and address these points.↩

- I like bellicose framings, but one could use neutral metaphors instead: “…making mediocre moves, reducing the EA community’s ability to do good together”, or more flowery ones “…making mediocre moves, reducing the EA’s community to flourish and give birth to valuable projects.”↩

- Incidentally, this is why providing criticism of EA is not a catch-22 where you thereby “are” “an EA”, or “are doing effective altruism”. In particular, you can agree with some of the philosophical attitudes and positions of Effective Altruism, without thereby having to pledge allegiance to the EA machine.↩

- E.g., technically, Open Philanthropy is its own thing, and the vehicle for Moskovitz’s donations is Good Ventures. But who cares.↩

- For example, per here, Open Philanthropy donated $450M in 2021. Did other sources of funding cumulative add to more than $45M? My guess is no, and that the distribution of funding is steep. For example, Jan Tallinn donated $23M in 2021. So the EA movement wouldn’t literally be a monopsony, but still, because capital is so concentrated, it seems like capital has much more power compared to labour.↩

- There are going to be some free variables, e.g., around what the “exchange rates” or conversion factors between money, illness and death should be, or around how to value a young person’s life vs an older person’s. But you can be transparent and predictable about how you will resolve these ambiguities.↩

- these are going to be grant officers at Open Philanthropy, but also EA Fund managers, people in charge of hiring decisions at CEA and at large EA organizations, and so on.↩

- Readers are also welcome to hypothesize what dynamics arise when trust is scarce. Perhaps promotion to incompetence across the people that are trusted? Or exacerbation of inner circle dynamics?↩

- You can solve this problem by having grant-makers be anonymous. Here is a robinhansonian design: have a cohort of anonymous regrantors and allow members of the public to make $20k bets at 1:2 odds on whether any one particular person is a grant-maker. This ensures that your regrantors will remain anonymous. Anonymous philanthropy has precedents, see e.g., here.↩

- Doesn’t seem like a great attachment theory setup.↩

- Incidentally, having romantic relationships with Open Philanthropy employees increases access to that coterie. That is, I suspect that having a close relationship with Open Phil people privileges the hypothesis that your grant is worth evaluation.↩

-

For some confirmatory evidence,In addition, note that Luke Muehlhauser, an Open Philanthropy grantmaker, is a board member at Anthropic. Muehlhauser emailed to mention that this was an arms-length situation, and that he didn't get the board seat as a result of Moskovit's investment, as a previous version of this post hinted at.↩ - I find it interesting that when he left Open Philanthropy to start the FTX Future Fund, Nick Beckstead (with others) designed it to look completely different than the Open Philanthropy model: trusting independent and eclectic expert regrantors to make grants according to their judgment, evaluated on their performance, rather than hierarchies of grantmakers each restricted to a cause or sub-cause.↩

- See here for a more libertarian perspective which disagrees in emphasis with the Wikipedia page.↩

- and his wife’s↩